7-minute read

keywords: paleontology

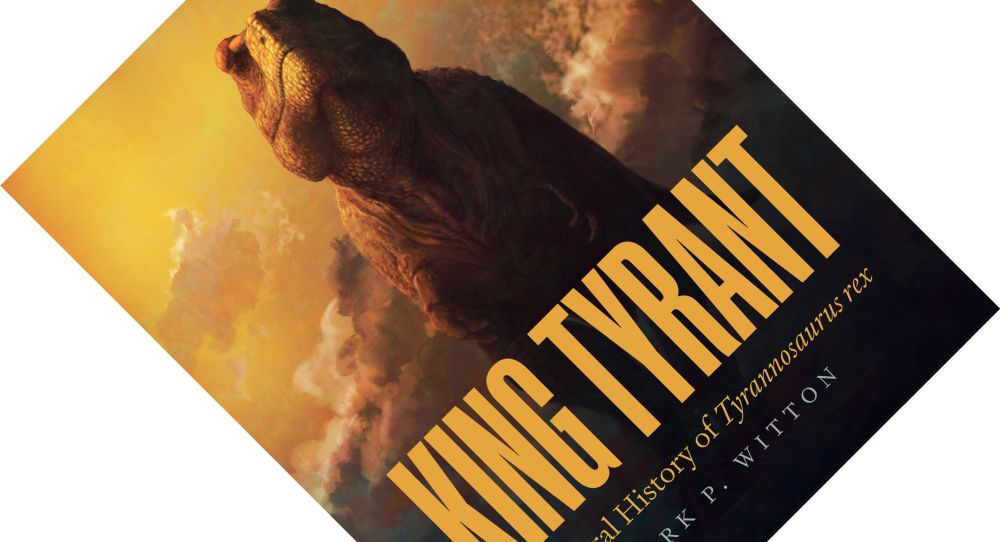

This review concludes a short series on theropod dinosaurs, having just read Gregory Paul’s The Princeton Field Guide to Predatory Dinosaurs and Dave Hone’s The Tyrannosaur Chronicles. When Princeton University Press announced King Tyrant, I was beyond excited. Whether it is pterosaurs, palaeoart, or the Crystal Palace dinosaurs; whatever palaeontologist and palaeoartist Mark Witton writes on has so far been brilliant, and King Tyrant very much continues that tradition. Do not let the pretty pictures fool you; this is not a children’s book but a grounded, fact-based overview of the scientific consensus on all things Tyrannosaurus rex, combined with numerous informative diagrams and Witton’s gorgeous palaeoart. The execution of this book sets the standard for what good popular science can be and is a model that other authors and publishers can aspire to.

King Tyrant: A Natural History of Tyrannosaurus rex, written by Mark P. Witton, published by Princeton University Press in May 2025 (hardback, 320 pages)

Even if you know nothing about dinosaurs, T. rex is the one name you will recognise, such is the fame of this extinct animal. Surely, books about it are a dime a dozen? In a recent interview on the Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs podcast, Witton pointed out that, surprisingly, this is not the case. Hone’s book covered the family at large, but, aside from two technical books in recent decades, the last popular treatment was Horner & Lessem’s book in 1993. That might just as well be prehistory, given how much research has advanced and how many more fossils have been found since then. This is a clear case of Witton writing the book that he wanted to read.

Even if you know nothing about dinosaurs, T. rex is the one name you will recognise, such is the fame of this extinct animal. Surely, books about it are a dime a dozen? In a recent interview on the Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs podcast, Witton pointed out that, surprisingly, this is not the case. Hone’s book covered the family at large, but, aside from two technical books in recent decades, the last popular treatment was Horner & Lessem’s book in 1993. That might just as well be prehistory, given how much research has advanced and how many more fossils have been found since then. This is a clear case of Witton writing the book that he wanted to read.

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts with eccentric fossil hunter Barnum Brown, who discovered the fossils, and especially Henry Fairfield Osborn, curator at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), who named the species. At a time when America’s robber barons were funding philanthropic institutions and museums to give their reputation a shine, spectacular displays of large dinosaur fossils were just the ticket to attract large crowds. Osborn was quick to see the potential of what they had and “the discovery and promotion of T. rex by the AMNH was proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. However, as Witton writes in his concluding statement, even though these popular depictions are often incredible, they “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279).

How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts with eccentric fossil hunter Barnum Brown, who discovered the fossils, and especially Henry Fairfield Osborn, curator at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), who named the species. At a time when America’s robber barons were funding philanthropic institutions and museums to give their reputation a shine, spectacular displays of large dinosaur fossils were just the ticket to attract large crowds. Osborn was quick to see the potential of what they had and “the discovery and promotion of T. rex by the AMNH was proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. However, as Witton writes in his concluding statement, even though these popular depictions are often incredible, they “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279).

“Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species and one of his most important goals with King Tyrant is to deconstruct hype and controversy.”

The bulk of the book thus explores what the science actually shows. The remaining six chapters flow logically into each other, following the same structure as Hone’s book: the definition and taxonomy of the species; internal and external anatomy; physiology, growth, sensory biology, locomotion, etc. (i.e., what all this anatomy might have been capable of); ecology and behaviour; and extinction. Indeed, the writing is one of the two highlights of this book. Witton strikes that fine balance between going into quite some technical detail and yet keeping it entertaining. The result is a well-grounded and accessible summary of the scientific consensus on numerous topics.

The bulk of the book thus explores what the science actually shows. The remaining six chapters flow logically into each other, following the same structure as Hone’s book: the definition and taxonomy of the species; internal and external anatomy; physiology, growth, sensory biology, locomotion, etc. (i.e., what all this anatomy might have been capable of); ecology and behaviour; and extinction. Indeed, the writing is one of the two highlights of this book. Witton strikes that fine balance between going into quite some technical detail and yet keeping it entertaining. The result is a well-grounded and accessible summary of the scientific consensus on numerous topics.

T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. As I have discovered while writing various reviews, opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.

In his book The Future of Dinosaurs, Hone pointed out the frequent disparity between what people think we know, and what we actually know—and plenty of examples of this feature here. Some confident depictions are almost completely fictitious. The trope of the roaring T. rex leads to the question of whether dinosaurs as a group vocalised at all! This is not “overzealous scientific conservatism” (p. 159); we have found, all told, one whole fossilised voice box. The ensuing discussion on the evolution of vocalisation in birds, dinosaurs, and other reptiles shows the complexities and competing scenarios. The opposite also holds: there are topics where the general public does not realise just how much palaeontologists know, such as the anatomy of T. rex‘s face or its remarkable growth pattern with age.

In his book The Future of Dinosaurs, Hone pointed out the frequent disparity between what people think we know, and what we actually know—and plenty of examples of this feature here. Some confident depictions are almost completely fictitious. The trope of the roaring T. rex leads to the question of whether dinosaurs as a group vocalised at all! This is not “overzealous scientific conservatism” (p. 159); we have found, all told, one whole fossilised voice box. The ensuing discussion on the evolution of vocalisation in birds, dinosaurs, and other reptiles shows the complexities and competing scenarios. The opposite also holds: there are topics where the general public does not realise just how much palaeontologists know, such as the anatomy of T. rex‘s face or its remarkable growth pattern with age.

“Witton has gone to the painstaking effort of redrawing every diagram, presenting them in a single unified style. I rate this attention to detail very highly.”

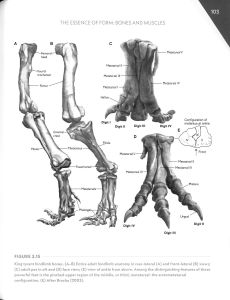

The other highlight of this book is the illustrations, both the artwork and the diagrams. Witton is an accomplished palaeoartist who cares deeply about the scientific accuracy of his artwork. We thus get modern depictions of dinosaurs with fleshy lips and bulky muscles. Each of these paintings is worthy of a frame, and it is hard to pick favourites. The book’s cover, showing T. rex rumbling a closed-mouth vocalisation (a behaviour seen in modern birds and reptiles), is, in my opinion, one of the best pieces he has ever made. The azhdarchid pterosaur stalking a juvenile T. rex on page 250 is also instantly memorable. Even when the subjects are cliché, such as T. rex near erupting volcanoes or the K–Pg impactor streaking across the sky, Witton’s depictions are visually arresting. Labelled photomontages show T. rex‘s “raw osteological charisma” (p. 4), and include detailed close-ups that help you form a mental picture of what all those anatomical bits look like. Equally important are the numerous informative diagrams littered throughout the book. Witton has gone to the painstaking effort of redrawing every one of them, in the process modifying and adapting them as necessary. Instead of a mishmash of styles, ages, production values, and extraneous details, the illustrations are presented in a single unified style. It will have been a huge amount of work for something that most authors and editors would probably consider nominal gains, but it shows his attention to detail, and I, for one, rate this very highly.

Even when the subjects are cliché, such as T. rex near erupting volcanoes or the K–Pg impactor streaking across the sky, Witton’s depictions are visually arresting. Labelled photomontages show T. rex‘s “raw osteological charisma” (p. 4), and include detailed close-ups that help you form a mental picture of what all those anatomical bits look like. Equally important are the numerous informative diagrams littered throughout the book. Witton has gone to the painstaking effort of redrawing every one of them, in the process modifying and adapting them as necessary. Instead of a mishmash of styles, ages, production values, and extraneous details, the illustrations are presented in a single unified style. It will have been a huge amount of work for something that most authors and editors would probably consider nominal gains, but it shows his attention to detail, and I, for one, rate this very highly.

King Tyrant is an instant classic: I do not even care that much for T. rex per se, but the book’s brilliant execution immediately lands it a spot in my top 5 for 2025. A compulsory buy for dinosaur enthusiasts, this book is also a valuable overview for professional palaeontologists and an inspirational example of what excellent science communication looks like.

As I was wrapping up, I thought to myself that I really would not mind similarly thorough treatises for other groups. You can imagine my delight when I discovered that Hone and Witton are teaming up for Spinosaur Tales in November. This is in addition to (seemingly) another book that he is currently teasing on his Patreon.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

2 comments