History will forever associate Charles Darwin with the theory of evolution, but the idea was in the air. Had not Darwin published his famous book, someone else would have likely snatched the prize. Husband-and-wife duo John and Mary Gribbin here examine the wider milieu in which Darwin operated and the many thinkers who preceded him. Given their previous collaborations, the first two parts of On the Origin of Evolution read like a well-oiled machine, but the book falters when they turn their eyes to the legacy of Darwin’s ideas.

On the Origin of Evolution: Tracing ‘Darwin’s Dangerous Idea’ from Aristotle to DNA, written by John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin, published in Europe by William Collins (a HarperCollins imprint) in November 2020 (hardback, 288 pages)

When you study the history of science, it seems there is just no way around Aristotle. In the context of this book, his legacy is the idea of the great chain of being: the notion that life can be ordered from simple to complex forms, with humans at the top as creation’s crowning glory. It was readily adopted by Christian thinkers and hamstrung evolutionary thinking for millennia.

Still, as the first third of this book shows, some people did ponder both man’s place in nature and the relationships between living beings. Liberally quoting from their writings, the authors introduce you to notable characters and their brilliant early flashes of insight. For example, Thomas Aquinas, writing in the 13th century, allowed for species to develop in their striving for perfection but rejected the idea of new ones arising after God’s act of creation. Fossils were long misunderstood, neither recognized as ancient nor as the remains of extinct creatures. I was therefore particularly fascinated by 17th-century British polymath Robert Hooke who may well have been one of the first to recognize fossils for what they were. His ideas on species formation and extinction seem prescient. In the 1770s, Lord Monboddo already argued that humans descended from apes. And yet, the dots were not connected into a bigger picture. Particular sticking points were extinction and the age of the Earth, a puzzle to which James Hutton and other geologists would later contribute much.

When the book gets to Darwin, the tempo slows right down and the middle third of the book examines Darwin’s life and simultaneous developments around him. The Gribbins sketch how Darwin, ever careful, worked on his ideas for decades, also because he felt that, as a geologist, one could not “examine the question of species who has not minutely described many” (p. 134). Something he subsequently spent years on. The history of how Alfred Russel Wallace later came to similar conclusions and ran them past Darwin in a letter, and how Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker presented both their work at a meeting of the Linnean Society, is well-known. What the Gribbins here clarify is that, if it seems strange to us now that Wallace’s letter was publicly presented by a third party without his consent, this was the custom of the time. Communications of scientific interest were expected to be made public as quickly as possible. Various quotes from Wallace indeed show nothing but a man who was very chuffed to have his work mentioned alongside Darwin’s.

“[…] the first two parts of On the Origin of Evolution read like a well-oiled machine, [numerous] details left me with the impression that the authors have been meticulous […]”

The Gribbins also pay attention to Erasmus Darwin (Charles’s grandfather) and relevant contemporaries such as Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Georges Cuvier. They give Lamarck his due and note the irony of him accepting evolution but denying extinction, and Cuvier denying evolution but accepting extinction. If the two had not ended up bitter enemies they might have put two and two together. Another lesser-known figure who came tantalisingly close, and virtually coined the term natural selection, was arborist Patrick Matthew who buried his thoughts in the appendix to a book on naval timber. Darwin was unaware of his work despite Matthew’s later public charges, the Gribbins write. Other notable details are a public admission to a change of heart over whether a letter from Darwin to Wallace was intended to warn Wallace off. The Gribbins used to think so, but are now persuaded it was not. They also clarify the oft-repeated factoid of On the Origin of Species selling out on the day of publication: “this is only true in the sense that all the copies had been bought up by the bookshops, ready to sell on to their customers” (p. 166). An observation that, working for a bookseller myself, rings true. These and other details left me with the impression that the authors have been meticulous up to this point. (I admit this is a risky thing to say; whole academic careers have been built on studying Wallace and Darwin’s lives, so cue people more knowledgeable than myself pointing out errors next).

On the Origin of Evolution competes for your attention with Rebecca Stott’s 2012 book Darwin’s Ghosts, which similarly traced Darwin’s intellectual forebears. That book ended with the above-mentioned presentation at the Linnean Society, so the Gribbins have the opportunity to set themselves apart with the last third of their book, which examines the development of Darwin’s ideas by later scientists. Although I enjoyed the book up to this point, the last part is where it fell a bit flat for me.

The Gribbins weave their narrative through the work of Gregor Mendel and its triple rediscovery decades later; the discovery of the structure of DNA, honouring the long course described in Unravelling the Double Helix; and the discovery of how DNA codes for amino acids. It touches on horizontal gene transfer, epigenetics, and twin studies and the discovery of polygenic traits. All important topics for sure, but they omit so many others as to make this part of their history rather haphazard.

“[…] the last third of their book, which examines the development of Darwin’s ideas by later scientists. […] omits so many [topics] as to make this part of their history rather haphazard.”

Two oversights stand out. They discuss how extinction ultimately became accepted but leave out the next chapter: the mass-extinction debates, which was a conflict between uniformitarianism and catastrophism. Similarly, they recognize Wallace as the grandfather of biogeography but leave out how the long-resisted idea of plate tectonics explained palaeobiogeographic patterns. Basically, they completely ignore the rise of palaeobiology and its contributions to evolution. Beyond these, they mention horizontal gene transfer, but not Carl Woese and his proposal of a Last Universal Common Ancestor. They feature Thomas Hunt Morgan’s research on Drosophila, but not the emergence of evolutionary developmental biology. They profile Barbara McClintock’s struggle to get her discovery of mobile genetic elements accepted but not Lynn Margulis‘s struggle to get endosymbiosis recognized. And although the Sources and Further Reading section lists other major thinkers, there is no discussion of, say, Ernst Mayr and the problem with species definitions, the work of Stephen Jay Gould, or the debate on levels of selection. Sexual selection and phylogenetics are completely absent.

They cram this last part in a mere 70 pages while repeatedly mentioning not being able to go deeper. I am not sure why. At 253 pages of text, the book is not particularly long. Had they spent another 50 or even 100 pages, I feel they could have done it more justice. I will be the first to concur that writing such an overview is challenging. Part of the problem, I think, is that the authors (John a science journalist with a PhD in astrophysics, Mary a teacher) do not have a thorough background in (molecular) biology and reach into unfamiliar territory, as evidenced by some elementary mistakes. On p. 218 they mention DNA contains three purines and one pyrimidine, and correct themselves two sentences later (there are two of each). They mix up the DNA base pairs on p. 226 (CT and AG pairs) but get it right on p. 227. And on p. 244 they mention the human genome consists of 6 billion base pairs which is double the actual number. Anyone who has had to study Alberts’s brick will have had these facts drummed into them, but their acknowledgements are silent on whether fellow biologists provided feedback on the manuscript. Now, I do not want to blow a few factual errors out of proportion, but together with the brevity of the material included, and the many other topics not covered, this last part left me less than satisfied.

Overall then, this book is an excellent introduction to the history of evolution before and up to Darwin that retains important detail despite being relatively brief. I was less impressed with the coverage on the developments since Darwin, which would benefit from supplementary reading. I hope a future review of The Black Box of Biology will fill in some of the blanks regarding molecular biology.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

After three previous books in this format on fossils, rocks, and dinosaurs, geologist and palaeontologist Donald R. Prothero here tackles the story of evolution in 25 notable discoveries. More so than the previous trio, this book tries to be a servant to two masters, resulting in a mixed bag.

The Story of Evolution in 25 Discoveries: The Evidence and the People Who Found It, written by Donald R. Prothero, published by Columbia University Press in December 2020 (hardback, 360 pages)

Prothero has organised The Story of Evolution in 25 Discoveries in a logical fashion. After convincing the reader that the universe and our planet are, indeed, really old, he considers some of Darwin’s lines of evidence for evolution, followed by several great transitions in evolution as revealed by the fossil record, more recent evidence from genetics and molecular biology, and, of course, evidence for the evolution of humans.

As in his previous books, Prothero manages to dig up some remarkable stories. For example, Darwin initially mistook the finches on the Galápagos for wrens, blackbirds, and other species. Only when he handed them to the famous ornithologist John Gould for a second opinion did it become clear that these were all finch species adapted to local conditions on the different islands. It later fell to others such as Peter and Rosemary Grant to do the long-term studies that elevated them to the icon of evolution they have become. Meanwhile, Othniel Charles Marsh’s monograph on primitive birds that still had teeth was unexpectedly branded a waste of taxpayer’s money when US congress was looking for excuses to cut funding to the US Geological Survey in the 1890s.

In many places, Prothero is careful and balanced in his coverage. He highlights the contribution of the historically overlooked Alfred Russel Wallace who independently hit on the idea of natural selection after Darwin had already been labouring on it for decades. And while Ernst Haeckel was accused of fraud over his famous drawings showing the embryonic development of different vertebrates, Prothero explains how there is a kernel of truth to Haeckel’s claim that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, even if “he may have been a bit overzealous in his drawings” (p. 69). On Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and his ideas, Prothero clarifies how there was much more to him than the caricature of the “guy who got evolution wrong” (p. 198) that he became.

“In many places, Prothero is careful and balanced in his coverage […] he clarifies how there was much more to Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck […] than the caricature of the “guy who got evolution wrong””

There are classic topics such as convergent evolution, the evolution of the eye, and Lynn Margulis and her theory of endosymbiosis. The relatively young branch of evolutionary developmental biology and the discovery of Hox genes showed that, actually, yes, nature does make leaps and does not always result in slow and gradual changes. Throughout, Prothero repeatedly reminds you that the evolutionary relationships between organisms are like a bush, and not a linear progression from primitive to more advanced creatures. He explains that evolution does not always result in perfect adaptations—they only have to be good enough to help in producing the next generation. And he points out that natural selection can only ever work with the material at hand, resulting in many jury-rigged contrivances, including in humans.

Now, Prothero is also a noted sceptic. A good deal of this book has the secondary aim of showing that creationism is an utterly flawed idea and that the evidence for evolution reveals no traces of intelligent design whatsoever. The thing is, he already did this exercise in Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters, so does it need repeating? He spends no fewer than seven chapters here on examples of transitional fossils that provide a detailed picture of fish leaving the water, whales returning to it, birds evolving from dinosaurs, giraffes evolving longer necks and elephants longer trunks, horses losing their toes and snakes their legs, and turtles acquiring shells. You almost get the feeling that he just cannot help himself.

I have few gripes with the topics that Prothero chose to include here, but I felt somewhat disappointed by all the topics he left out as a consequence of this secondary mission. Two notable omissions are the process of domestication, even though Darwin used numerous examples of it in On the Origin of Species and then wrote a separate book about it. The same is true for Darwin’s other big idea: there is no mention of sexual selection, sperm competition, or mate choice.

“[…] this book has the secondary aim of showing that creationism is an utterly flawed idea […] but I felt somewhat disappointed by all the topics he left out as a consequence […]”

Beyond these, there is little on speciation and biodiversity, the formation of higher taxa, or the difficulty with species concepts. Epigenetics is mentioned, but not by name. The textbook example of the peppered moth is included, but there is no further discussion on camouflage, mimicry, or warning signals. Richard Dawkins has to make do with two brief mentions, but there is nothing about the different levels of selection, whether selfish genes or group selection. And I am sure Prothero could have beautifully explained the difference between the modern and extended syntheses.

The focus on convincing the reader of the evidence against design raises the question of who this book is written for. For evolutionary biologists like myself, Prothero is preaching to the choir, while creationists are unlikely to pick this book up. The best this might achieve is to remind biologists of the evidence for evolution if we ever find ourselves debating creationists.

Prothero is a fantastic science communicator, and I really enjoy this format of 25 vignettes by which to examine the many facets of a topic. The material that he did choose to include is written with verve and balance. In my opinion, however, the dual motive underlying The Story of Evolution in 25 Discoveries means that he left out many relevant topics and has written a book of narrower focus than the title might suggest.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>Can we predict what aliens will look like? On some level, no, which has given science fiction writers the liberty to let their imagination run wild. On another level, yes, writes zoologist Arik Kershenbaum. But we need to stop focusing on form and start focusing on function. There are universal laws of biology that help us understand why life is the way it is, and they are the subject of this book. If you are concerned that consideration of life’s most fundamental properties will make for a dense read, don’t panic, The Zoologist’s Guide to the Galaxy is a spine-tingling dive into astrobiology that I could not put down.

The Zoologist’s Guide to the Galaxy: What Animals on Earth Reveal about Aliens – and Ourselves, written by Arik Kershenbaum, published by Viking in September 2020 (hardback, 356 pages)

Fundamental to answering the question of what alien life might be like, Kershenbaum argues, is to recognize that evolution by natural selection is the most important law in biology, “an inevitable mechanism, not just restricted to planet Earth” (p. 8). Rather than trying to answer particulars (Will aliens have two legs? Six? Or none?), he focuses on process: “Movement, communication, cooperation: these are evolutionary outcomes that are solutions to universal problems” (p. 11). Thus each chapter discusses “some feature of animal behaviour on Earth that is not unique to Earth—that can’t be unique to Earth” (p. 14). These three quotes nail down how Kershenbaum managed to hook me in right from the start of his book.

A key observation to support his argument that natural selection will not be limited to planet Earth is convergent evolution. I find this one of the most exciting topics in evolutionary biology and have written about it extensively last year when reviewing three books in The Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology from MIT Press. Brief refresher should you need it: convergent evolution refers to the ubiquitous pattern of evolution repeatedly hitting on the same or similar solutions to a problem in different organisms. Kershenbaum introduces it here with some examples and also touches on the contingency vs. convergence debate, of which Stephen Jay Gould and Simon Conway Morris are the most prominent spokesmen. Convergent evolution can hold lessons for astrobiology, though George R. McGhee’s book Convergent Evolution on Earth did not quite deliver on its promise to do so. Kershenbaum, however, does. There is no reason to think that convergent evolution would be limited to life on Earth because “we live in a universe where not everything is possible” (p. 46). The laws of physics circumscribe a limited set of possibilities, something that Charles Cockell so memorably expressed by writing that “physics is life’s silent commander“.

So what are these characteristics that we can expect to evolve universally? Kershenbaum considers six, from very basic to likely rarer: movement, communication, intelligence, cooperation, information exchange, and language. Even though these are very fundamental properties of life that you could talk about in abstract terms, what makes The Zoologist’s Guide to the Galaxy so accessible is Kershenbaum’s pithy writing style. I will highlight three examples to give you a taster.

“[Kershenbaum] focuses on process: “Movement, communication, cooperation: these are evolutionary outcomes that are solutions to universal problems“”

Take movement: “We move because we must, not because we can […] Life needs energy, and if energy is not evenly distributed, life must go in search of it” (p. 70–72). Earth life has tried pretty much every mechanism we can think of to move in a fluid medium (air or water) or on the interface between a fluid and a solid, so expect alien life forms to float, paddle, or develop legs.

Cooperation similarly seems likely. There is a range of benefits to individuals cooperating, not in the least the threat of predation. “Predation is universal, because no ecosystem can exist for long without someone trying to take a bite out of somebody else; the selective pressure on acquiring as much energy as possible is just too strong” (p. 171). When and whether it is evolutionarily advantageous to evolve cooperation is something we can answer mathematically using game theory, “a simple technique, applicable on any planet” (p. 192). We should not be surprised to find aliens with complex social structures, dominance hierarchies, and reciprocal behaviour.

A full-blown language, on the other hand, seems uniquely human. This chapter leads you through the difficulty in defining language and grammar, the contentious topic of language evolution, and an interesting dive into xenolinguistics, or how you would recognize whether a signal carries the signature of language. These are all areas of active research where no consensus has been reached between different schools of thought. Nevertheless, Kershenbaum identifies two fundamental features that an alien language would have: it is a means to communicate complex concepts, and it evolved by natural selection.

“There is no reason to think that convergent evolution would be limited to life on Earth because “we live in a universe where not everything is possible“. The laws of physics circumscribe a limited set of possibilities […]”

This core of six chapters is padded out with a fascinating chapter that considers artificial life forms. After all, evolution as we know it acts blindly, without foresight. “But what if it were all different? What would life look like if it did know where it was going?” (p. 258). Well, perhaps not all that different. “Game theory […] is ruthlessly inevitable” (p. 280), so expect conflict and cooperation. Furthermore “some things like mutation, and even death, can’t be eliminated just by being incredibly smart” (p. 286).

The whole is bookended by two more philosophical chapters. The first asks what an animal is and whether aliens would be considered animals. Though we would not share ancestry, the point of this book is to show that we would likely share fundamental processes and properties. The last chapter considers the impact that the discovery of alien life would have on us and whether we would recognize such life forms as a fellow form of humanity. Throughout, there are footnotes to general literature, and an annotated list of suggested reading provides plenty of material if you want to delve deeper.

Kershenbaum admits that you probably wanted him to tell you what aliens look like, and his book contains less speculative zoology than e.g. Imagined Life. However, by the same logic of giving a man a fish vs. teaching him how to fish, understanding the rules that life follows is ultimately more rewarding. Kershenbaum’s smooth writing style makes it a proper page-turner.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>When I recently reviewed The Real Planet of the Apes, I casually wrote how that book dealt with the evolution of Old Work monkeys and apes, ignoring New World monkeys which went off on their own evolutionary experiment in South America. But that did leave me wondering. Those New World monkeys, what did they get up to then? Here, primatologist Alfred L. Rosenberger provides a comprehensive and incredibly accessible book that showed these monkeys to be far more fascinating than I imagined.

New World Monkeys: The Evolutionary Odyssey, written by Alfred L. Rosenberger, published by Princeton University Press in September 2020 (hardback, 350 pages)

Most people are probably not very familiar with these monkeys. Technically known as platyrrhines, they are predominantly arboreal (i.e. living in trees), small to medium-sized primates. You might know the insanely loud howler monkeys from nature documentaries. Perhaps you have heard of capuchin monkeys or spider monkeys. But you could be forgiven for not having heard of marmosets and tamarins, or the even more obscurely named titis, sakis, and uacaris. A total of 16 genera are recognized, but outside of the scientific literature and abovementioned technical books, these monkeys are not all that well known. And that is a shame as, from an evolutionary perspective, this is a unique group.

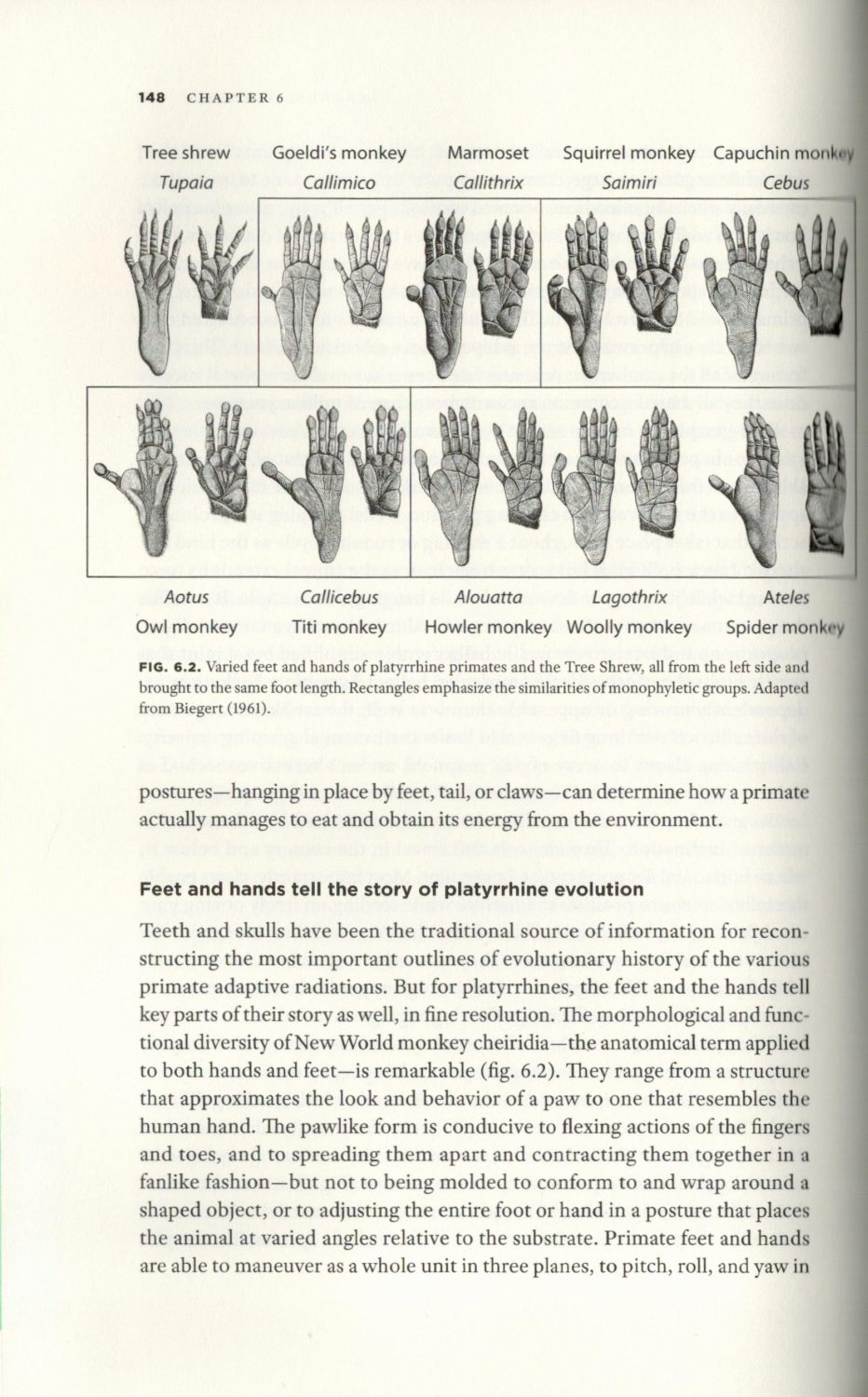

Now, before Rosenberger gets to this, it helps to better know these monkeys. Accompanied by many excellent illustrations and photos, the first half of New World Monkeys is dedicated to their ecology, behaviour, and morphology. Topics covered include their diet and dentition; locomotion and the anatomy of hands, feet, and prehensile tails; but also brain size and shape; and their social organization and ways of communicating via sight, sound, and smell.

Now, before Rosenberger gets to this, it helps to better know these monkeys. Accompanied by many excellent illustrations and photos, the first half of New World Monkeys is dedicated to their ecology, behaviour, and morphology. Topics covered include their diet and dentition; locomotion and the anatomy of hands, feet, and prehensile tails; but also brain size and shape; and their social organization and ways of communicating via sight, sound, and smell.

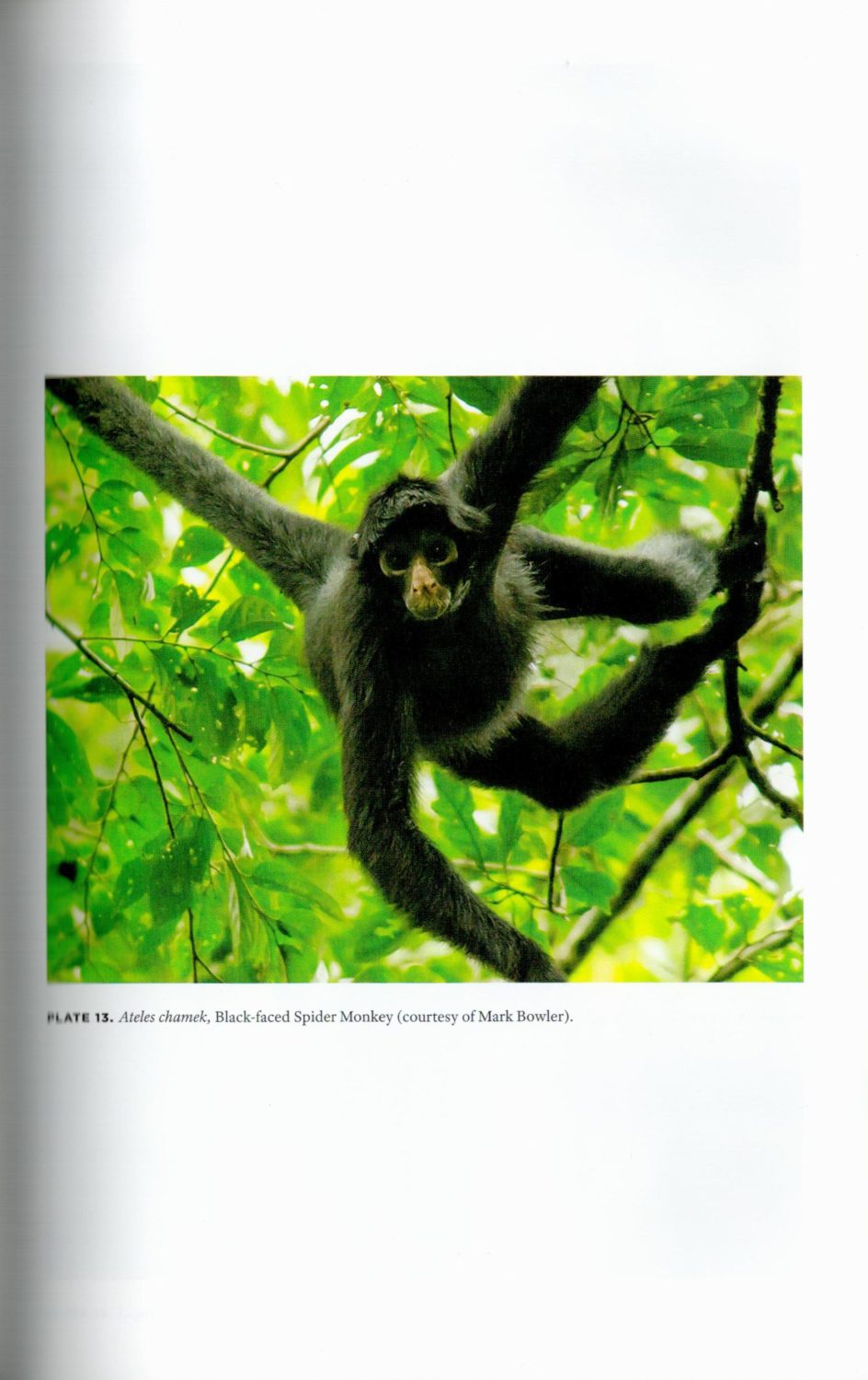

The platyrrhines are a diverse bunch with some remarkable specialisations. In the family Cebidae we find the smallest members, some of whom, the Marmosets and Pygmy Marmosets, have teeth specialized for gouging the bark of gum trees and feeding on the gum that is released in response. In the family Pitheciidae we find the only nocturnal member, the Owl Monkeys, which have concomitant morphological adaptations such as enlarged eyes. In both this and the closely related Titi Monkeys, individuals have the adorable habit of twining their tails when e.g. socializing or sleeping. The family Atelidae is home to species with exceptionally prehensile tails whose underside ends in a pad with a fingertip-like surface. The Muriquis and the aptly-named Spider Monkeys use them as a fifth limb in locomotion, as demonstrated by a striking photo of a Black-faced Spider Monkey on plate 13. Here we also find the well-known Howler Monkeys, whose skull is heavily modified to support the exceptionally loud vocal organs in their throat and neck.

“[…] the whole radiation has been remarkably stable for at least 20 million years. Today’s New World monkeys are virtually unchanged from their ancestors […] This stands in sharp contrast to the evolutionary history of Old World monkeys […]”

Despite these differences, platyrrhines are closely related and form what is called an adaptive radiation. Just like the textbook example of Darwin’s finches, many members have evolved unique adaptations and ways of living to minimise competition and maximise resource partitioning. Two ideas feature prominently in this book to explain how platyrrhines have evolved and what makes this adaptive radiation both so diverse and so interesting.

One idea is what Rosenberger calls the Ecophylogenetics Hypothesis. If I have understood him correctly, this combines information on a species’s ecology and phylogeny, its evolutionary relationships. It can offer hypotheses on how ecological interactions have evolved, but it also recognizes that ecological adaptations are shaped and constrained by evolutionary relatedness. For the platyrrhines, taxonomically related members are also ecologically similar. To quote Rosenberger: “[…] phylogenetic relatedness literally breeds resemblance in form, ecology, and behavior” (p. 96) and “Each of the major taxonomic groups that we define phylogenetically is also an ecological unit […]” (p. 97).

One idea is what Rosenberger calls the Ecophylogenetics Hypothesis. If I have understood him correctly, this combines information on a species’s ecology and phylogeny, its evolutionary relationships. It can offer hypotheses on how ecological interactions have evolved, but it also recognizes that ecological adaptations are shaped and constrained by evolutionary relatedness. For the platyrrhines, taxonomically related members are also ecologically similar. To quote Rosenberger: “[…] phylogenetic relatedness literally breeds resemblance in form, ecology, and behavior” (p. 96) and “Each of the major taxonomic groups that we define phylogenetically is also an ecological unit […]” (p. 97).

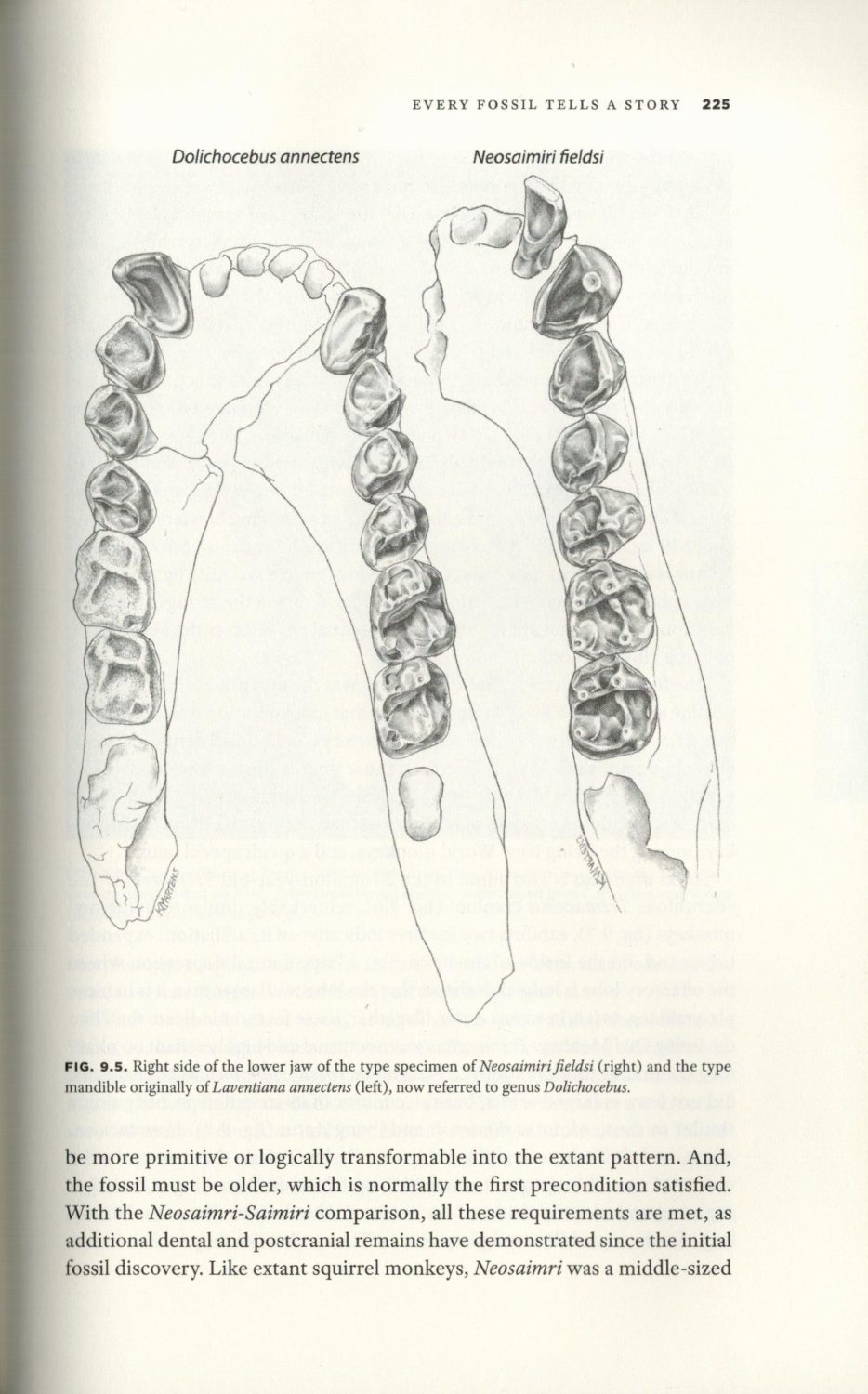

The other idea that makes the platyrrhines so interesting is dubbed the Long-Lineage Hypothesis. An extensive chapter on the fossil record documents how the whole radiation has been remarkably stable for at least 20 million years. Today’s New World monkeys are virtually unchanged from their ancestors, living the same lifestyles and occupying the same ecological niches. Some fossils have even been classified in the same genus as their living counterparts. This stands in sharp contrast to the evolutionary history of Old World monkeys where there has been a constant churn, whole groups of primates evolving and going extinct with time.

“Without ever losing academic rigour or intellectual depth, Rosenberger quietly proves himself to be a natural-born teacher and storyteller […]”

What stands out, especially when Rosenberger starts talking taxonomy and evolution, is how well-written and accessible the material here is. He takes his time to enlighten you on the history, utility, and inner workings of zoological nomenclature, making the observation that “names can reflect evolutionary hypotheses“. Here, finally, I read clear explanations of terms such as incertae sedis (of uncertain taxonomic placement), monotypic genera (a genus consisting of only a single species), or neotypes (a replacement type specimen). Similarly, there are carefully wrapped lessons on how science is done—on the distinction between scenarios and hypotheses, or how parsimony and explanatory efficiency are important when formulating hypotheses.  Without ever losing academic rigour or intellectual depth, Rosenberger quietly proves himself to be a natural-born teacher and storyteller, seamlessly blending in the occasional amusing anecdote.

Without ever losing academic rigour or intellectual depth, Rosenberger quietly proves himself to be a natural-born teacher and storyteller, seamlessly blending in the occasional amusing anecdote.

A final two short chapters conclude the book. One draws on the very interesting question of biogeography, i.e. on how platyrrhine ancestors ended up in South America, which was long an island continent. Rosenberger convincingly argues against the popular notion of monkeys crossing the Atlantic on rafts of vegetation* and in favour of more gradual overland dispersal. The other chapter highlights their conservation plight as much of their tropical forest habitat has been destroyed by humans.

With New World Monkeys, Rosenberger draws on his 50+ years of professional experience to authoritatively synthesize a large body of literature. As such, this book is invaluable to primatologists and evolutionary biologists and should be the first port of call for anyone wanting to find out more about the origins, evolution, and behaviour of these South and Central American primates.

* One mechanism that Rosenberger does not mention is that tsunamis could be behind transoceanic rafting, as argued in a recent Science paper. This looked at marine species in particular and I doubt it would make much of a difference for terrestrial species. Most of the objections Rosenberger gives would still apply.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

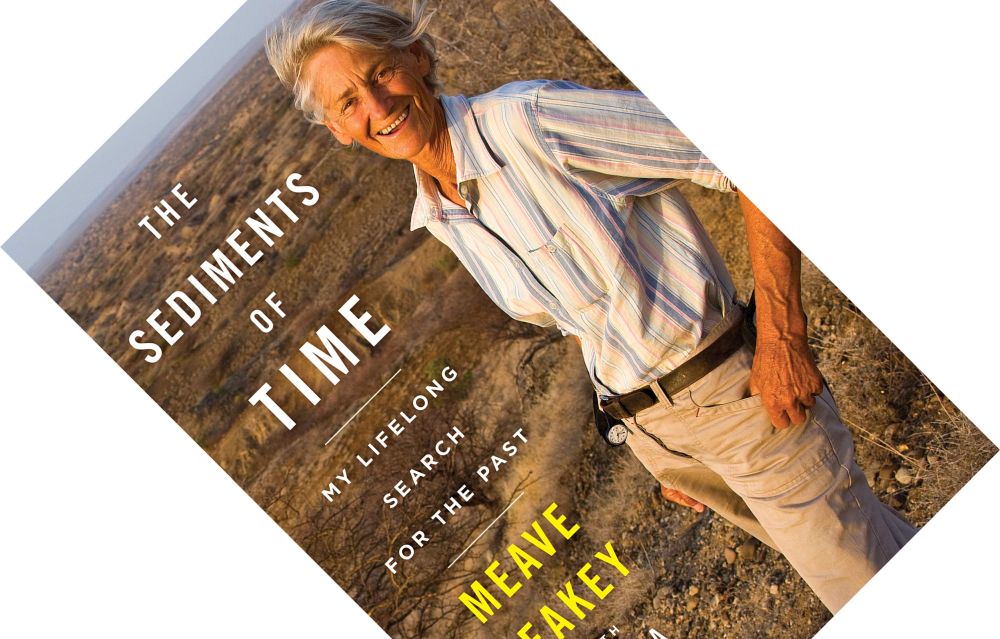

]]>In the field of palaeoanthropology, one name keeps turning up: the Leakey dynasty. Since Louis Leakey’s first excavations in 1926, three generations of this family have been involved in anthropological research in East Africa. In this captivating memoir, Meave, a second-generation Leakey, reflects on a lifetime of fieldwork and research and provides an inspirational blueprint for what women can achieve in science.

The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past, written by Meave Leakey and Samira Leakey, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in November 2020 (hardback, 396 pages)

With The Sediments of Time, Meave* follows a family tradition. Her husband Richard, and his parents Louis and Mary have all been the subject of (auto)biographies, now many decades old. Science writer Virginia Morell later portrayed the whole family in her 1999 book Ancestral Passions. Much has happened in the meantime, and though this book portrays Meave’s personal life, it heavily leans towards presenting her professional achievements, as well as scientific advances in the discipline at large. Thus, Meave’s childhood and early youth are succinctly described in the first 15-page chapter as she is keen to get to 1965 when a 23-year-old Meave starts working with Louis in Kenya.

Whereas Louis and Mary were famous for their work in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Richard and Meave have made their careers around Lake Turkana in northern Kenya. The first two parts of the book take the reader chronologically through the various excavation campaigns. These include the decade-long excavations in and around Koobi Fora, one highlight of which was the find of Nariokotome Boy (also known as Turkana Boy), a largely complete skeleton of a young Homo erectus. The subsequent campaign in Lothagam yielded little hominin material but did reveal a well-documented faunal turnover of herbivore browsers being replaced by grazers with time. Meave has also described several new hominin species. This includes Australopithecus anamensis, which would be ancestral to Australopithecus afarensis (represented by the famous Lucy skeleton), and Kenyanthropus platyops, which would be of the same age as Ardipithecus ramidus. That last name might sound familiar, because…

“Woven into Meave’s narrative of exploration and excavation is an overview of how palaeoanthropology developed as a discipline, and what are some of its big outstanding questions.”

Having just reviewed Fossil Men, which portrayed the notorious palaeoanthropologist Tim White, I was curious to see what Meave had to say about him. In Fossil Men, Kermit Pattison already mentioned that she described White “with a note of sympathy” (p. 5), and she affirms that picture here, writing that he is “a meticulous scientist […] intolerant of bad science […] outspoken and frank […] although he was charming and a gentleman in less formal situations” (p. 136). And though they meet more than once to compare fossils, notes, and ideas, they remain at loggerheads over certain claims.

Woven into Meave’s narrative of exploration and excavation is an overview of how palaeoanthropology developed as a discipline, and what are some of its big outstanding questions. A recurrent theme is the influence of climate on evolution, often by impacting diet and available food sources. There is the difficult question of naming species and how much difference is enough to recognise a separate species, which ties into the whole lumpers vs. splitters debate in taxonomy. The latter readily name new species whereas the former (White being an example) point to sexual dimorphism and morphological variation and recognize only one or very few hominin species. Your stance in that debate affects what you think of Meave’s descriptions of Au. anamensis as being part of a lineage towards Au. afarensis, and whether K. platyops is a species distinct from Ar. ramidus (White obviously thinks not).

This discussion of topics relevant to palaeoanthropology strongly comes to the fore in the book’s third part, by which time Meave is examining the Homo lineage and the question where we appeared from. This sees her tackling topics such as human childbirth and the role of grandmothers, Lieberman’s hypothesis of endurance running as a uniquely human strategy to run prey to exhaustion, palaeoclimatology and the mechanism of the Milankovitch cycles, the spread of Homo erectus around the globe (the Out of Africa I hypothesis), and the use of genetics to trace deep human ancestry. I feel that Meave overstretches herself a little bit in places here. Though her explanations are lucid and include some good illustrations, some relevant recent literature, on e.g. ancient DNA and Neanderthals is not mentioned.

“Meave can draw on a deep pool of remarkable and amusing anecdotes that are put to good use to lighten up the text. And though the focus is on her professional achievements and the science, real life interrupts work on numerous occasions.”

Meave can draw on a deep pool of remarkable and amusing anecdotes that are put to good use to lighten up the text. And though the focus is on her professional achievements and the science, real life interrupts work on numerous occasions. Some of these are joyful, such as the birth of her daughters Louise and Samira. Some are a mixed blessing, such as Richard’s career changes, first when Kenya’s president hand-picks him to lead the Kenya Wildlife Service and combat rampant elephant poaching, then when he switches to attempting political reform. It removes him from palaeoanthropology and their time together in the field. Other occasions are outright harrowing, such as Richard’s faltering kidneys that require transplantations, or the horrific plane crash that sees him ultimately lose both legs despite extended surgery.

Illustrator Patricia Wynne contributes some tasteful drawings to this book, though the figure legends do not always clarify the important details these images try to convey. And I would have loved to see some photos of important specimens, whether during excavation or after preparation, especially given how much Meave focuses on the scientific story in this book. Many specimens are described in great detail but the colour plate section mostly contains photos of the Leakeys and collaborators in the field. Another minor point of criticism is that I was not clear on Samira’s part in writing this book. The dustjacket mentions her as a co-author, but the story is told exclusively through Meave’s eyes, and the acknowledgements do not clarify Samira’s role. I am left to surmise that Meave and Samira together drew on their store of memories for this book.

These minor criticisms notwithstanding, I found The Sediments of Time an inspiring memoir that provided a (for myself long-overdue) introduction to the Leakey dynasty. Meave has led a charmed existence and she is a fantastic role model for women in science.

* I normally refer to authors by their last name but, for obvious reasons and with all due respect, I will be deviating from that habit here and mention the various Leakeys by their first name.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

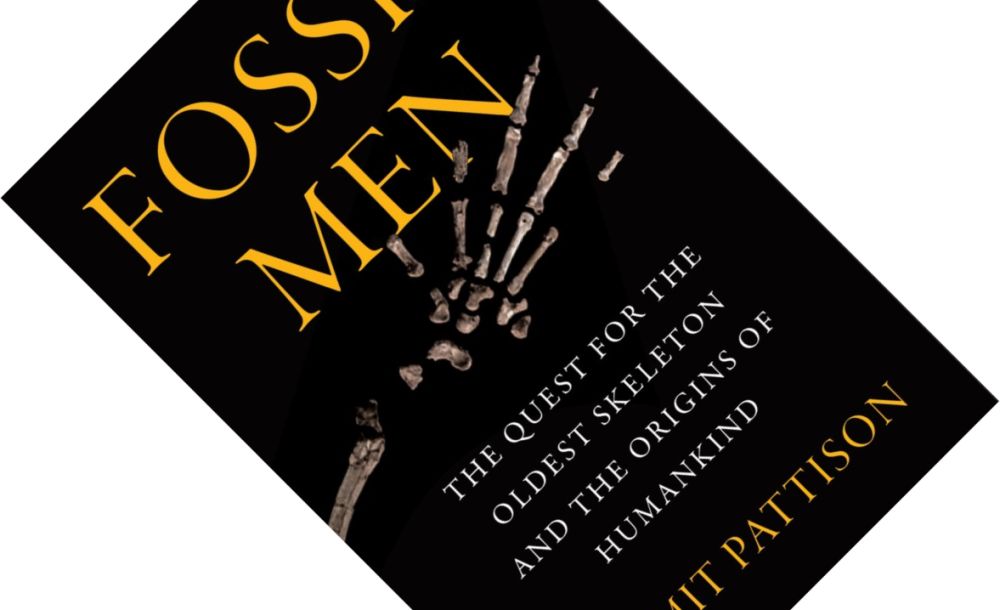

]]>When thinking of human ancestors, the name “Lucy” will likely come to mind. But a dedicated team of scientists spent decades labouring on the discovery of a species more than a million years older still, at 4.4 million years of age. Nicknamed “Ardi” and classified as Ardipithecus ramidus, it was finally revealed to the world in 2009. For a full decade, journalist Kermit Pattison immersed himself in the story of Ardi’s discovery to bring to life both the science and the scientists. The resulting Fossil Men is an incredibly well-researched book that tells the definitive insider’s story of how one of the most divisive fossils in palaeoanthropology was discovered by one of its most divisive characters: Tim White.

Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind, written by Kermit Pattison, published by William Morrow & Co. in December 2020 (hardback, 534 pages)

Fossil Men stands out for its brutally honest portrayal of the main protagonist, Tim White, something for which Pattison has had the full cooperation of White, his co-workers, and his many adversaries. From the very first pages, he is unsparingly described as a relentless perfectionist with “a razor intellect, hair-trigger bullshit detector, short temper, long list of discoveries, and longer list of enemies” (p. 2). He will take as long as he darn well needs to make sure his findings are beyond bulletproof. And while many loathe being at the receiving end of his withering criticism—”enemies not only resented him; they fucking hated him” (p. 71)—many also admit that he excels at what he does: “Tim White is brutal. He’s a real scientist. His literature will stay forever” (p. 4).

Pattison follows White’s story of fossil discovery in Ethiopia from its start in 1981. Against a backdrop of bureaucracy, corruption, and civil wars, White organised annual expeditions that “he micromanaged without apology“, while fellow anthropologist Bruce Latimer marvels that he is “without question the best field worker there is […] His science, logistics, and efficiency are phenomenal” (p. 127). What stands out, and endeared him to this reader, is how he insists on local capacity building, employing and training numerous Ethiopians, and only rarely recruiting foreigners, the Japanese Gen Suwa being one of these notable exceptions.

As a journalist who has published in the New York Times, GQ, and other outlets, it comes as no surprise that Pattison engagingly portrays the human interest story. He has extensively interviewed the people around White, including Ethiopian collaborators such as Berhane Asfaw, Alemu Ademassu, and Yohannes Haile-Selassie, or the creationist-turned-palaeoanthropologist Owen Lovejoy. But he also speaks to White’s many adversaries, including Ian Tattersall, Lucy team members Jon Kalb and the celebrity-loving Don Johanson, as well as members of the world-famous Leakey dynasty.

“Fossil Men stands out for its brutally honest portrayal of the main protagonist, Tim White”

What positively surprised me, however, was how thoroughly and accurately Pattison delves into the biological details. Whether it is related species such as Ardipithecus kadabba, the anatomy of the foot and spine, or the genetical wonderland of ancient DNA, evolutionary developmental biology, or comparative genomics—he puts to good use the more than 500 pages that have been crammed into Fossil Men. White’s obsessive attention to detail seems to have rubbed off on Pattison, and in the acknowledgements he admits the enormity of writing this book: “Nobody in their right mind takes on a project like this” (p. 423). The bibliography reveals just how deeply he has ventured: next to books and peer-reviewed papers, Pattison has consulted unpublished manuscripts, interviews, grant proposals, video material, oral histories, court files, and archives of private correspondence.

Over the years, White’s team unearths fragmentary remains and puzzles together the creature that will become known as Ardi. However, much to the frustration of peers and grant agencies, White refuses to go public until he has every detail nailed down. This is not a popular strategy and the briefly-featured Michel Brunet was similarly scolded in Ancient Bones for holding back important material. After an initial 1994 announcement in Nature, White and collaborators labour for a full 15 years in strict secrecy. Pattison here exclusively reports the many twists, turns, and realisations during this long period.

The crescendo of Fossil Men comes with the big reveal of Ardi in a 2009 special issue of Science. As expected, the popular press laps it up while the academic establishment is initially more resistant. Pattison again excels at showcasing the range of opinions. Reading the objections it is easy to see how White’s arguments go against the grain. Specifically, A. ramidus was initially considered to be the most chimp-like ancestor known so far. However, the more White’s team looked at the anatomy of the feet, pelvis, skull, and other body parts, the more they argued that human ancestors never went through a stage resembling modern apes. The long-held paradigm that modern apes are good models of our human ancestors was declared dead. Instead, compared to Ardi, humans are the ones retaining primitive anatomical aspects, while modern African apes are considered evolutionarily more derived. It would require several instances of convergent evolution amongst apes for this to happen, and is thus considered less parsimonious by evolutionary biologists, but that does not mean it is impossible.

“Ardi, it seems, has everyone flummoxed, proving to be “a simian-human combination that nobody had predicted“”

Ardi, it seems, has everyone flummoxed, proving to be “a simian-human combination that nobody had predicted” (p. 353). Refreshingly, some opponents have come around to White’s arguments after they have been given the opportunity to inspect the fossils for themselves. Another supporter is David Begun who dedicated a section to A. ramidus in The Real Planet of the Apes, discussing the configuration of the big toe. He agrees with White that “meticulous collection of data should come before interpretation“, and highlights how the assumption that hominin ancestors by definition cannot have a grasping big toe imposes restrictions on how to interpret new and contradictory evidence such as Ardi.

Arguments over Ardi’s status continue unabated. While writing this review, New Scientist reported on a study in Science Advances that analysed Ardi’s hands, arguing that they are more chimp-like and adapted for swinging from branches (suspensory locomotion). Unsurprisingly, White has responded to this in his usual gruff fashion: “This is another failed resurrection of the antiquated notion that living chimpanzees are good models for our ancestors“.

I admit that I was initially mildly concerned that the publisher was overselling Fossil Men by calling it a scientific detective story. However, it did not take long for me to become completely engrossed by Pattison’s portrayal of these scientists, and to be in awe of the skill with which he tackles numerous complex biological topics. This is a chunky book, but it is a page-turner that you will not regret.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>Where do humanity’s evolutionary roots lie? The answer has long been “in Africa”, but this idea is being challenged from various sides. I previously reviewed Begun’s The Real Planet of the Apes as a warming-up exercise before delving into this book. My conclusion was that its discussion of archaic ape evolution, although proposing that species moved back and forth between Africa and Eurasia, ultimately did not really challenge the Out of Africa hypothesis. Not so Ancient Bones. German palaeontologist Madeleine Böhme, With the help of two co-authors, journalists Rüdiger Braun and Florian Breier, firmly challenges the established narrative in an intriguing book that is as outspoken as it is readable.

Ancient Bones: Unearthing the Astonishing New Story of How We Became Human, written by Madelaine Böhme, Rüdiger Braun, and Florian Breier, published by Greystone Books in September 2020 (hardback, 376 pages)

Ancient Bones was originally published in German in November 2019 as Wie wir Menschen wurden. Less than a year later the good folk at Greystone Books have already published the English translation. The challenge to the Out of Africa narrative is twofold here: criticism by palaeoanthropologists and Böhme’s own discoveries. The latter are the novel part of this book and are told with much verve. Two fossils, in particular, take centre-stage.

First, there is the rediscovery of a tooth and a jawbone christened Graecopithecus freybergi. Originally found in 1944 near Athens, together with other animal fossils, they went missing for decades before Böhme tracks them down, in true Raiders-of-the-Lost-Ark–style, in the catacombs of the Nuremberg congress hall, a location infamous for the Nazi party rallies during World War II. With today’s technology, old fossils hold new value. Careful study of the jawbone with computed tomography scanning showed that the teeth resembled early hominins* more than other great ape fossils. Novel magnetostratigraphic analysis of crystals in sediment trapped inside the animal bones from the same dig allowed the whole lot to be dated to about 7.2 million years ago (mya).

“These two important fossils, Graecopithecus and Danuvius, were present in Europe at a time where conventional wisdom has it that Africa was the epicentre of hominin evolution.”

The second discovery is made by Böhme and collaborators in a southern German clay pit. In a nail-biting race against time—the pit is commercially operated year-round to turn the clay into bricks—they manage to recover much fossil material during three field seasons. This includes a partial skeleton of a new primate species named Danuvius guggenmosi dated to about 11.6 mya. Based on several physical characteristics, Böhme and colleagues argue it, too, resembles early hominins more than known great ape fossils.

So, Graecopithecus and Danuvius, two important fossils, are one part of her argument that there were early hominins in Europe at a period where conventional wisdom has it that Africa was the epicentre of hominin evolution. The second challenge to the Out of Africa hypothesis comes from other palaeoanthropologists. For example, there is criticism of the earliest claimed African hominin, Sahelantropus tchadensis**, with some researchers arguing it is a great ape instead. Then there are several fossils from Asia (the Chinese Homo wushanensis, the Philippine H. luzonensis, and the Indonesian H. floresiensis), plus tools that overlap with the African timeline up to 2.6 mya, contradicting the Out of Africa hypothesis (specifically, the Out of Africa I variant).

“As with deserts, savannah ecosystems were in constant flux and integrated across Africa and Eurasia, a region dubbed Savannahstan by some. Perhaps that was the cradle of humanity.”

This criticism is embedded in plenty of background information that benefits tremendously from excellent infographics by freelance illustrator Nadine Gibler. Some topics covered are the history palaeoanthropological discoveries that, thanks in particular to the Leakey dynasty, shifted in focus from Europe and Asia to Africa from 1924 onwards. There is a recap of the history of archaic ape evolution that Begun told in The Real Planet of the Apes. And there is an overview of the anatomical characters that set apart apes and hominins.

Particularly relevant is the palaeoclimatological and biogeographical story. On the one hand, shrinking and growing deserts throughout northern Africa, the Mediterranean, and Asia provided a barrier to migration. On the other hand, the little known Messinian Salinity Crisis*** saw the Mediterranean Sea dry up about 5.6 mya, allowing migration of fauna between Africa and Eurasia, including a lot of animals we now think of as “typically” African. “Why should early hominins be an exception?” asks Böhme on page 194. As with deserts, savannah ecosystems were in constant flux and integrated across Africa and Eurasia, a region dubbed Savannahstan by some. Perhaps that was the cradle of humanity.

“It is not that the fossils found in Africa are not important, but […] the focus on any one particular continent is too narrow […]”

This material is divided over seventeen reasonably-sized, readable chapters in four parts. Depending on how widely you have read on human evolution, the final two parts of the book will already be familiar to you and feel like filler or will be a tasty sampler of other topics. Böhme changes gear here, introducing two questions. One, what made us human? She briefly discusses the hand, above-mentioned Asian Homo fossils and our wanderlust, long-distance running, Wrangham’s thesis that fire and cooking allowed our brains to grow larger, and the physical and genetic evidence for language (this section is a far cry from Rudolf Botha’s critical evaluation in Neanderthal Language). Two, why are we the last ape standing? Rather than Paul Martin’s Pleistocene overkill hypothesis, she favours the (to me novel) idea that that at least Neanderthals and Denisovans simply merged with us. Ancient DNA has revealed we all carry some of their DNA in us, but we do not all have the same pieces. Puzzle it all together, and an estimated 30% of the Neanderthal genome and up to 90% of the Denisovan genome is retained in the current human population.

Ancient Bones is not afraid to go against the grain and be provocative. Though it will no doubt ruffle feathers, my impression is that Böhme draws on a growing body of convincing evidence and arguments to make her case. It is not that the fossils found in Africa are not important, but Böhme’s conclusion on page 271 that the focus on any one particular continent is too narrow is hard to disagree with in light of everything she presents here. What is undeniable is that her decision to involve three others in the writing process makes this a top-notch example of an engaging book accessible to a broad audience.

*Hominins are a taxonomical grouping encompassing humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos, plus their extinct ancestors.

**There is a remarkable personal attack here on Sahelanthropus‘s discoverer who has withheld a thighbone from scrutiny by the wider scientific community for close to two decades pending his own investigations. It could answer whether Sahelanthropus was bipedal or not. When two scientists wanted to present our understanding so far at a meeting their application was rejected. “Could it be that Michel Brunet, one of the icons of French science, Knight of the Légion d’honneur, recipient of the Ordre national du Merité, did not want to be challenged?” (p. 128), is one of the things Böhme asks pointedly. Now, it is not that there are no big egos in science, because there are, but to publicly shame a colleague in a book for a general audience felt, to me, unnecessary. It would have been sufficient to write, as she does here, that his choice is unfortunate and holds back scientific progress.

***The Messinian Salinity Crisis is a fascinating geological event that cries out for a popular treatment. Though some books mention it, as far as I am aware, there has not been a book dedicated to it since 1983, even though our knowledge on it has increased tremendously.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>In his previous book, Beyond Words, ecologist Carl Safina convinced his readers of the rich inner lives of animals. Just like we do, they have thoughts, feelings, and emotions. But the similarities do not stop there. Becoming Wild focuses on animal culture, the social knowledge that is transmitted between individuals and generations through sharing and learning. The more we look, the more animals seem less different from us—or we from them. On top of that, Safina puts forward several eye-opening and previously-overlooked implications of animal culture.

Becoming Wild: How Animals Learn to be Animals, written by Carl Safina, published in Europe by Oneworld Publications in April 2020 (hardback, 377 pages)

To observe animal culture first-hand, Safina focuses on three species and accompanies the researchers that study them in the field. He furthermore draws on the primary scientific literature on culture in a host of other species. The stars of this book are sperm whales and the long-term Dominica Sperm Whale Project led by Shane Gero, the scarlet macaws in Peru studied by Don Brightsmith and Gaby Vigo’s group, and the chimpanzees in Uganda’s Budongo Forest studied by Cat Hobaiter’s group. They are worth the price of admission alone.

I admit I have a thing for the denizens of the deep. Just as Safina previously showed orcas to be fascinating, here he taught me how little I know about sperm whales. Clearly, I must read up on them. They communicate in clicks generated by the world’s most powerful animal sonar. Beyond finding squid in the deep, unique patterns of clicks (so-called codas) announce group membership to other whales. Sperm whale families worldwide are organised in different clans that do not mingle, each sounding their own coda. And these have to be learned by youngsters. Safina furthermore gives a searing history of whaling and its effects and considers what we know of culture in other cetaceans.

It is hard not to like parrots, and the section on macaws provides plenty of antics to enjoy. These pair-bonding birds teach their young where food is to be found and what ripens when. Sodium is in short supply in this part of the jungle, so macaws use ancient clay deposits as communal salt licks. But this is also an opportunity to socialise, find mates, and see who is hanging out with who. Here, too, groups of parrots have idiosyncratic cultural preferences for certain salt licks over others.

“The three stars of this book—sperm whales, scarlet macaws, and chimpanzees—are worth the price of admission alone.”

Chimpanzees, then, have been intensively studied and examples of culture abound. Different groups have unique tool use and dietary habits that get passed down the generations, not just through copying, but at times even through teaching. Some chimps use rocks as anvils and hammers to crack nuts, some craft wooden spears to kill bush babies hiding inside logs, while others raid nearby farms for guava fruit that most chimps will not touch. They live in strongly hierarchical groups where alpha males vie for power, and violent outbursts are frequent. Youngsters have to be taught everybody’s place in the ranking as they grow up. Nevertheless, Cat Hobaiter is at pains to show Safina that most of the time these animals are peaceful. Based on this, primary literature, and books such as The New Chimpanzee and The Real Chimpanzee, Safina, in turn, paints a nuanced picture of chimpanzee society. Interested readers will also want to look out for the forthcoming Chimpanzee: Lessons from our Sister Species and Chimpanzees in Context for the state-of-the-art of the field.

But these three focus species are not all there is. Safina examines other studies to show how widespread animal culture is. He draws parallels between humans and other animals and probingly asks what this means for how we treat them and their world. Perhaps no more so than on page 327: “No wisdom tradition grants a generation permission to deplete the world and drive it toward ruin […] Life is a relay race, our task merely to pass the torch.” And he develops interesting ideas, two of which struck me as eye-opening.

One is the underrated significance of culture for conservation biology. Much of how animals learn to be animals depends on knowledge being passed from generation to generation. Thus, the biodiversity crisis is about more than just numerical losses, genetic bottlenecks, and habitat fragmentation. Unique cultures are snuffed out as we kill animals and destroy their habitats to claim more room for ourselves. Worse, breaking these links of knowledge transmission also greatly hinders reintroduction efforts. Without their elders to teach them how to live in their particular environments, young animals often struggle to survive, while willy-nilly translocating mature animals is bound to run into obstacles. It is a disheartening insight that, it seems to me, many conservation biologists and organisations still have to come to terms with.

“[…] the biodiversity crisis is about more than just numerical losses, genetic bottlenecks, and habitat fragmentation. Unique cultures are snuffed out as we kill animals and destroy their habitats to claim more room for ourselves”

The other concerns the role of culture in speciation and evolution. Safina hinted at this in Beyond Words but here develops this idea more fully. The evolution of new species starts with reproductive isolation between different groups, this much biologists agree on. But what drives reproductive isolation? Traditionally, geography is invoked: the formation of mountains and rivers, or the conquest of islands separates populations in space, preventing reproduction. If this persists, populations start to diverge and are on their way to becoming separate species. Biologists call this allopatric speciation. But there are cases, the Lake Victoria cichlids being a textbook example, where species continue to share the same habitat and could interbreed but for some reason do not. This is known as sympatric speciation. Biologists have long struggled to explain what causes reproductive isolation here.

Culture could.

As Safina points out, socially learned preferences lead to avoidance between groups and thus to reproductive isolation. In orcas, for example, different groups with different diets (fish vs. marine mammals) are already showing morphological changes. Safina proposes that, next to natural and sexual selection, cultural selection could be a pathway to speciation. It is a thought-provoking idea.

“[…] socially learned preferences lead to avoidance between groups and thus to reproductive isolation […] Safina proposes that, next to natural and sexual selection, cultural selection could be a pathway to speciation. “

What makes Becoming Wild such a pleasure to read is that Safina speaks to you in many voices. There is Safina the ecologist, Safina the conservationist, Safina the philosopher, etc. He has many angles on his subject which keeps the narrative flowing and the reader engaged. His questions are probing: Who are we sharing the planet with and what is life like for them? In places, his prose soars into poetry. When writing of the dawn chorus: “Dawn is the song that silence sings […] as the eyelash of daybreak rolls endlessly across the planet, a chorus of birds and monkeys is eternally greeting a new dawn.” (p. 232) And the epigraph that describes Shane Gero’s revelation as to why he studies sperm whales was so powerful that Safina had me in tears before even starting the book.

Becoming Wild is another jewel in the crown of Safina’s work that packs fascinating field studies, interesting theoretical ideas, soul-searching questions, and probing reflections on human and animal nature into a book that is as profound as it is moving.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>Recognising that animals are intelligent beings with inner lives, emotions—even personalities—has a troubled place in the history of ethology, the study of animal behaviour. For most pet owners, these things will seem self-evident, but ethologists have long been hostile to the idea of anthropomorphising animals by attributing human characteristics to them. The tide is turning, though, and on the back of decades-long careers, scientists such as Frans de Waal, Marc Bekoff, and Carl Safina have become well-known public voices breaking down this outdated taboo. In preparation of reviewing Safina’s new book Becoming Wild, I decided I should first read his bestseller Beyond Words. I have to issue an apology here: courtesy of the publisher Henry Holt I have had a review copy of this book for several years that gathered dust until now. And that was entirely my loss, as Beyond Words turned out to be a beautiful, moving book.

Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, written by Carl Safina, published in Europe by Souvenir Press in September 2016 (hardback, 480 pages)

A plain summary of this book could run something like this: a large book in four parts in which ecologist Carl Safina delves into the inner worlds of elephants, wolves, and orcas, with frequent comparisons to other animals. This is based on interviews with biologists, time spent with them in the field observing their study animals, and close reading of both the books they wrote and the primary scientific literature. In Africa, he speaks to Iain Douglas-Hamilton and Amboseli Elephant Research Project leader Cynthia Moss. In Yellowstone National Park he spends time with long-term wolf-watchers Laurie Lyman, Doug McLaughlin, and Rick McIntyre. The latter has since started chronicling the lives of Yellowstone’s alpha wolves in a yet-to-be-completed trilogy. And on the Pacific coast between the USA and Canada he accompanies Ken Balcomb who has dedicated his life to observing orcas, while listening closely to Erich Hoyt, Alexandra Morton, Denise Herzing, and Diana Reiss.

This summary would tell you of the long-term studies and numerous observations that have revealed so much. How elephants in a herd defer to the leadership of a matriarch, who is a walking memory bank of valuable knowledge on e.g. the location of food and water holes in times of famine and drought. How they show empathy by caring for their wounded and sick, even grieving their dead, paying close attention to bones long after the death of their owner. How they communicate, using infrasound to cover long distances, and how the slaughter for ivory causes life-long havoc by destroying family structures.

The wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park have revealed how the different alpha males and females have their own personalities, some ruling their pack calmly, others tyrannically. These are clever carnivores who outsmart competitors threatening their pups, and cooperate in a complex fashion to bring down large prey. Here, too, human hunters killing wolves causes collateral damage that reverberates down the social hierarchy, breaking up and reshuffling packs, often costing more lives.

“Not assuming that other animals have thoughts and feelings was a good start for a new science. Insisting they did not was bad science.”

And killer whales? These highly social and long-lived marine mammals live in pods that, like other cetaceans, show what can only be called culture. Such as their exceptional dietary specialisation that is taught to youngsters. These echo-locating predators show refined, cooperative hunting techniques and are intensely social, mothers contributing to the survival of their children and grandchildren well after menopause. Just as elephants and wolves, they recognize other individuals after prolonged periods of separation (and show it too). As told elsewhere, we learned much of this the hard way by catching killer whales for display in marine theme parks. Suffice to say that breaking up families and isolating individuals in small pools has turned out to be extremely traumatising.

But this way of reviewing the book would neglect much of what makes it such an exceptional read. And I am not talking about all the other intelligent beings populating these pages: the primates, dogs, dolphins, and birds.

Take the much-needed history lesson of why scientists have been so shy to grant animals a measure of agency and intelligence: the mere mention of it could kill your academic career. In Mama’s Last Hug, Frans de Waal called this resistance to anthropomorphising “anthropodenial”. Safina agrees that we have taken it to the other extreme: “Not assuming that other animals have thoughts and feelings was a good start for a new science. Insisting they did not was bad science” (p. 27). Notably, though, where De Waal makes a careful distinction between emotions and feelings, Safina uses these two words interchangeably.

“Peel back the skin and underneath we find similarities everywhere […] and why would we expect anything else? We know that evolution excels at reusing, repurposing, and rejiggling existing structures and processes.”

Or what of the gentle skewering of academic concepts such as “theory of mind”, the realisation that others have their own motivations and desires? Those who continue to deny animals this should get out more, for they show “that many humans lack a theory of mind for non-humans” (p. 253). In Safina’s hands, the mirror mark test, that supposed litmus test of self-awareness, looks daft. Animals failing to recognize their own reflection only show that they do not understand reflection, without it, well, reflecting on self-awareness. In the wild, both self-awareness and gauging another’s state of mind are often a matter of life or death.

Probably one of the most convincing threads that runs through this book, and to which Safina returns frequently, is that of evolutionary legacy. Consciousness, emotion—the mental traits that we long thought as uniquely human—have deep roots. Peel back the skin and underneath we find similarities everywhere: the same neurological circuits, the same hormones, the same physiological pathways. And why would we expect anything else? We know that evolution excels at reusing, repurposing, and rejiggling existing structures and processes.

So, he happily goes against the grain and speculates about animals’ mental experience in this book, though always with one eye on evidence, logic, and science. (He helpfully bundles up the more unbelievable ones on cetaceans in a chapter called “Woo-Woo”.) To really see animals not for what, but for who they are, observations outside of the artificial environments of laboratories and captive enclosures are vital. Consequently, as Safina admits, much of what he relates here is anecdotal. As many sceptical scientists, myself included, like to say: “the plural of anecdote is not data”. But the bin in his mind labelled “unlikely stories” is getting cluttered. Anecdotes can only keep piling up for so long before you can no longer ignore them.

“[T]his book would not have the impact it has had if it was not for the writing. It is easy to see why Safina’s oeuvre has garnered literary awards.”

Finally, this book would not have the impact it has had if it was not for the writing. It is easy to see why Safina’s oeuvre has garnered literary awards. His many, short chapters are threaded together suspensefully. His wordplay sometimes borders on brilliant: when observing our shared evolutionary history and legacy: “beneath the skin, kin” (p. 324); when pondering our endless cruelty towards animals: “the next step beyond human civilization: humane civilization” (p. 411). And if the many stories do not already move you, I will leave you with a quote that choked me up, where he makes the point that the study of animal behaviour is not a mere “boutique endeavour”:

“Anyone can read about how much we are losing. All the animals that human parents paint on nursery room walls, all the creatures depicted in paintings of Noah’s ark, are actually in mortal trouble now. Their flood is us. What I’ve tried to show is how other animals experience the lives they so energetically and so determinedly cling to. I wanted to know who these creatures are. Now we may feel, beneath our ribs, why they must live.” (p. 411)

Beyond Words is a heartfelt gem of a book. Whether you are fascinated by the lives of charismatic megafauna such as elephants, wolves, or killer whales, or have an interest in animal behaviour, pick up this book. It is never too late to read a bestseller that you have ignored so far.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>

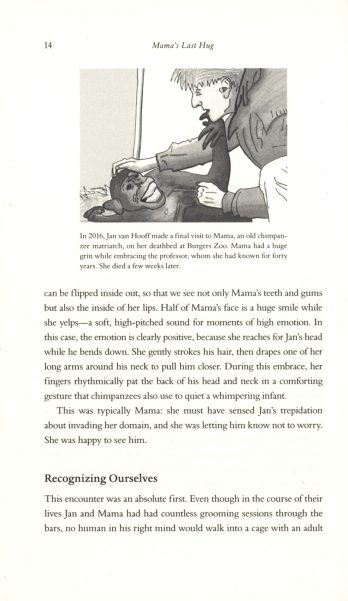

“Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Teach Us about Ourselves”, written by Frans de Waal, published in Europe by Granta Books in March 2019 (hardback, 348 pages)

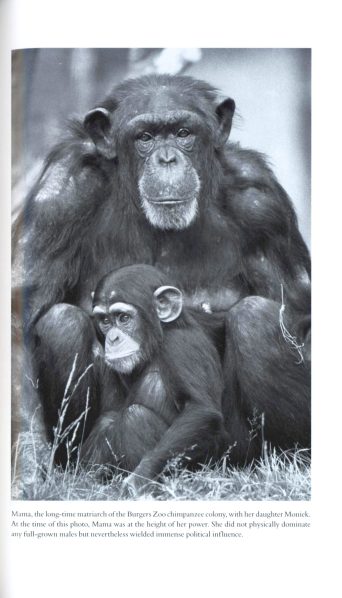

The book opens with the final meeting between the titular Mama, an old chimpanzee matriarch on her deathbed at Burgers Zoo in the Netherlands, and Dutch biologist Jan van Hooff, whom she had known for some 40 years. The video clip shows a touching moment of cross-species affection as Mama wakes up and suddenly recognizes Jan, hugging him. (As an aside, I do feel the book provides useful context you might not get from just watching it – most people, myself included, would not be able to interpret chimpanzee behaviour properly.)

Should we be surprised by Mama’s capability to recall Jan? De Waal is strongly of the opinion that the school of behaviourism pioneered by the likes of B.F. Skinner and others has cast a long shadow over the study of animal behaviour. They see animals merely as stimulus-response machines driven by instincts and simple learning, and De Waal’s previous book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? was a passionate riposte to this mode of thinking. Mama’s Last Hug is the companion to that book, dealing with emotions, which De Waal considers fully integrated with cognition and intelligence (see also Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain).

Should we be surprised by Mama’s capability to recall Jan? De Waal is strongly of the opinion that the school of behaviourism pioneered by the likes of B.F. Skinner and others has cast a long shadow over the study of animal behaviour. They see animals merely as stimulus-response machines driven by instincts and simple learning, and De Waal’s previous book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? was a passionate riposte to this mode of thinking. Mama’s Last Hug is the companion to that book, dealing with emotions, which De Waal considers fully integrated with cognition and intelligence (see also Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain).

Before we proceed there is an important distinction to be made that De Waal returns to throughout the book. Emotions and feelings are not the same things, though they are often conflated in day-to-day speech. Emotions are bodily and mental states (fear, anger, desire) that drive behaviour. They show as facial expressions, gestures, odours, or changes in skin colour or vocal timbre. Feelings are subjective internal states only known to those who have them. Or as De Waal poetically puts it: “We show our emotions, but we talk about our feelings”. Emotions, therefore, can be observed and measured in the wild or in experimental settings. Feelings… well, making claims on what animals feel is a bridge too far even for De Waal. He thinks it is likely animals related to us have similar feelings, but he also recognises that this is pure conjecture for the moment.

“Emotions and feelings are not the same things […]: “We show our emotions, but we talk about our feelings””

And with that, De Waal launches into his book. In seven chapters he wanders widely, discussing his own and other’s research on primates and other animals; recounting engaging anecdotes of observations made in the wild or in captivity; and weaving in history lessons, explaining how the academic landscape of ethology (the study of animal behaviour) started, how it developed, and what has changed over the many decades of his own research career.

In passing, he deals with a range of emotions. Grief is particularly well publicised for elephants (see How Animals Grieve). Laughing and smiling are argued by Van Hooff to express different emotions in primates, but to have grown closer and often blend in humans. Empathy (sensitivity to another’s emotions) is widely documented in primates, where group members regularly comfort each other (see also De Waal’s earlier book The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society). And the list goes on: disgust, shame, guilt, pride, hope, wrath, forgiveness, gratitude, envy… De Waal shows how all of these have been observed primates and other mammals (see also Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel). And where researchers have cared to look, some also show up in birds and fish (see Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave Like Humans and What a Fish Knows: The Inner Lives of Our Underwater Cousins).