What is the price of humanity’s progress? The cover of this book, featuring a dusty landscape of tree stumps, leaves little to the imagination. In the eyes of French journalist and historian Laurent Testot it has been nothing short of cataclysmic. Originally published in French in 2017, The University of Chicago Press published the English translation at the tail-end of 2020.

Early on, Testot makes clear that environmental history as a discipline can take several forms: studying both the impact of humans on the environment, and of the environment on human affairs, as well as putting nature in a historical context. Testot does all of this in this ambitious book as he charts the exploits of Monkey—his metaphor for humanity—through seven revolutions and three million years.

Cataclysms: An Environmental History of Humanity, written by Laurent Testot, published by The University of Chicago Press in November 2020 (hardback, 452 pages)

To be frank, Testot deals with the first 2,988,000 years in the first two chapters. Understandably, as the pace of progress was initially slow, and comparatively little information is available to us from the palaeontological and archaeological records. Thus, he starts his history proper with the agricultural revolution ~12,000 years ago. Given the synthesizing nature of this book, Cataclysms will be a feast of recognition for readers that are familiar with the literature.

Some examples include the near-simultaneous rise of agriculture in several places, with geography playing an important role in which plants and animals were available to domesticate, or the fall of the Late-Bronze Age civilizations in the 12th century BCE. The myth of virgin rainforests and the long history of agriculture practised in the jungle. The microbiological onslaught that accompanied the Columbian exchange when Christopher Columbus and other explorers brought new epidemics to the Americas, or the scourge of mosquito-borne diseases that later decimated European colonialists overseas. The medieval Little Ice Age and the global crises it precipitated, or the worldwide impact of the Tambora volcanic eruption. The Great Acceleration in the 20th century and the recognition of the Anthropocene. All of these have been chronicled at length in books and other publications.

“Given the synthesizing nature of this book, Cataclysms will be a feast of recognition for readers that are familiar with the literature.”

Testot also mentions episodes that I was barely familiar with; partially, I suspect, because he can draw on the French history literature. For example the eruption of the Samalas volcano that seems to have served as a transition between the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. Or the 15th-century mining for silver in the Andes and the immense pollution that caused. Or the environmental roots of the expression “mad as a hatter” (it involves the 17th-century beaver trade). Cataclysms sometimes seems to forget it is an environmental history book. Thus, the environment takes a backseat when he describes the Axial Age, the period between 800 and 300 BCE that saw the birth of universal religions and philosophies in both Asia and Europe that are still with us today. Similarly, the chapter charting the rise of money, empires, and trade in Europe and Asia before the Common Era only at the very end examines the environmental impact of it all.

The book’s style might divide opinions. Testot throws all his eggs in the proverbial narrative basket. The book is clearly deeply researched, but the notes section at the end encompasses a mere 16 pages. Testot must have decided that supporting every claim and fact with a footnote would have distracted from the story he tells. Although the references contain many interesting books and publications, those wishing to check up on certain claims will have to do their own research. Furthermore, the book is strikingly devoid of photos, maps, graphs, and tables, bar a single chart of the human world population through time in the appendix. As such, I felt Cataclysms did not deliver on the dustjacket’s promise of providing “the full tally” the way e.g. Vaclav Smil did in Harvesting the Biosphere. Those wanting a more data-driven overview will probably want to check out Cataclysms‘s big contender for 2020, Daniel R. Headrick’s Humans versus Nature. I had the chance to rifle through a copy, though not yet read it in full. At 604 pages with a 100-page notes section (and some illustrations), it promises to be a denser read.

“[The book] will undoubtedly charm newcomers to the field with its narrative style and ambitious scope […] but I suspect that seasoned readers will crave something more dense and data-heavy.”

Testot’s outlook for the future is bleak, though his concluding chapter wanders somewhat aimlessly. Rather than offering an overview of which planetary boundaries we have breached and how far in overshoot we are, Testot focuses on what he calls the upcoming Evolutive Revolution before turning to some likely consequences of climate change. This final revolution could either pan out as the pipe-dream of transhumanism where nano-, bio-, and information technologies converge into the singularity that would make humans immortal / obsolete as Artificial Intelligence takes over (something Testot is critical of), or we may end up as mutants in the chemical cesspit that we are making of our planet. Throw in a conclusion and an epilogue to the English edition that both reiterate main points from the book, and it starts to feel a little bit like Tolkien’s struggle to let the reader go in the last book of The Lord of the Rings.

Environmental history has become a rather crowded subject and opinions will probably be divided on whether Cataclysms stands out from the crowd sufficiently. It will undoubtedly charm newcomers to the field with its narrative style and ambitious scope—Testot knows how to spin a fine yarn and provides an entry point to many fascinating chapters in world history that readers will want to explore further. I certainly enjoyed reading it, but I suspect that seasoned readers will crave something more dense and data-heavy.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>Having just read Barash’s Through a Glass Brightly, it seemed logical to next read The Selfish Ape by biologist Nicholas P. Money. With the dustjacket calling the human being Homo narcissus, and the book “a refreshing response to common fantasies about the ascent of humanity“, these two clearly explore the same ideas, though one look at the cover suggests a darker tone. Money mostly takes the reader on a tour of human biology to show how we are little different from our fellow creatures, spicing up his writing with bleak observations. This one, my friend, sees through the glass darkly…

The Selfish Ape: Human Nature and Our Path to Extinction, written by Nicholas P. Money, published by Reaktion Books in July 2019 (hardback, 148 pages)

Money pulls no punches in this book, his preface labelling humanity as “cosmic vandals“. And not ten pages into the book he is already discussing antinatalism, seeing parenthood as a questionable virtue and noting how “the birth of ever more human beings with the capacity for suffering adds to the collective horror in the universe“.

Having set the tone for the book, Money proceeds to take the reader on a brief tour through deep time, charting how our planet became habitable and how life evolved, before settling on human biology. These chapters see him explain our physiology, neurobiology, genetics, reproduction, embryology, ageing, and dying. He does so with admirable brevity and sometimes exquisitely compact definitions and metaphors.

“Money […] revels in casting humans back amongst the animals […] “humans have more moving parts than worms, but the individual cells that make them are equally complicated“”

Thus entropy is “the physical process that makes a mess of everything“, while Money explains the gene-centric view of evolution by saying that “we are temporary vessels for genes, situated in family trees that assume the shape of a river delta with DNA streams draining down from ancestors to descendants“. The discovery of DNA and its structure is a particular highlight for him and in just a few pages he mentions some of the key players in that 100-year history that Williams so elaborately described in Unravelling the Double Helix.

Money livens up his writing with quotes from literature and poetry, such as Shakespeare’s work and Milton’s Paradise Lost, and seemingly revels in casting humans back amongst the animals. Our bodies a mineral frame hung with stringy bands of protein and blobs of fat. Our genomes containing fewer genes than many plants. Our mental capacities shared with a menagerie of birds and mammals that have been shown capable of tool use, self-awareness, and emotions. Or what to make of the sharp observation that “humans have more moving parts than worms, but the individual cells that make them are equally complicated“. Yet “we swan around as if we owned the place“.

“having lots of children in this day and age is nothing less than “an act of environmental terrorism“”

Money’s mild tone in the central part of the book is almost at odds with the misanthropic fury he has reserved for the last few chapters. Regular readers will have noticed how I see overpopulation as the root cause of many of our planetary woes. In my opinion, Money is right on the, well, money when he notes that “besides the environmental impact of the head count, the luxuries of modern life multiply the planetary damage“. Merely ascertaining this is not enough for him though. With climate change spiralling out of control, “the greatest contribution that an individual can make to reducing greenhouse gas emissions is to be dead. Failing this, the next best thing is to abstain from manufacturing babies“. While having lots of children in this day and age is nothing less than “an act of environmental terrorism“.

Did you just splutter your coffee all over your keyboard?

Think of this what you will – I think Money puts his finger on a very sore spot (one that drives me up the wall) when writing that “the relationship between population growth and environmental degradation is neglected in public discourse“, whether by politicians, economists, or environmental activists. How appropriate an observation amidst the current brouhaha around Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg. As much as I admire her for speaking up, the near helpless and hysterical tone of “do something!” the whole debate is taking on is not helpful. And no, writes Money, “charitable contributions” such as solar panels and electric cars will not cut it, they are mere “funeral decorations for Earth“. So, the sooner we can move on from that, the better.

“Money puts his finger on a very sore spot (one that drives me up the wall) when writing that “the relationship between population growth and environmental degradation is neglected in public discourse“”

Despite Money’s provocative statements, or more likely because of them, I greatly enjoyed The Selfish Ape, speaking as it did to the misanthrope and antinatalist in me (my reading list on this encompassing books such as Why Have Children?, Debating Procreation, Permissible Progeny?, and One Child). The Selfish Ape is unrelentingly bleak in its outlook – if my favourite blogger Mark Manson had written this book, he might have simply called it “Everything is Fucked” and dropped the subtitle “A Book About Hope“. Money might have thrown in his lot with the likes of Roy Scranton, but I do not feel quite that destitute yet. With mainstream outlets such as The New York Times publishing pieces titled “No Children Because of Climate Change? Some People Are Considering It” the tide might be turning.

The decision to package this powerful punch in just 110 pages is, I think, both admirable and wise, minimising audience fatigue. I wonder if there are points in this book where Money risks losing the sympathy of a part of his audience, though I also think his message is too important to worry much about that – offending a few sensitive snowflakes is a small price to pay. It strikes me that it is still largely taboo to talk of the links between overpopulation, natalism, and environmental degradation. Thrusting this taboo into the limelight is, for me, the real power of this book.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

You can support this blog using below affiliate links, as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases:

or ebook

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>

“Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology“, written by Adrienne Mayor, published by Princeton University Press in October 2018 (hardback, 304 pages)

Before going in, just a few words on what this book is not. Though the title might suggest a historical overview of ancient automata, Mayor limits herself to Greek mythology, with some accounts from ancient India and China thrown in the mix. You will not find mediaeval automata here (see e.g. Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art), and do not expect mention of Leonardo da Vinci (for an introduction, see e.g. Leonardo’s Machines: Secrets and Inventions in the Da Vinci Codex).

Similarly, the focus is as much on the myths and the ancient dreams of the subtitle, as it is on the machines. So those interested in the engineering and mechanical details, Mayor writes on this in the last chapter, but this book might not quite be what you hoped for. As she explains, the ancient Greeks imagined their gods capable of crafting robots without necessarily explaining how these were supposed to work, the gods’ expertise being beyond scrutiny. This area is not my speciality, but good starting points might instead be The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, the somewhat dated Technology in the Ancient World and Engineering in the Ancient World, and the hard-to-find Ancient Greek Technology: The Inventions of the Ancient Greeks.

Similarly, the focus is as much on the myths and the ancient dreams of the subtitle, as it is on the machines. So those interested in the engineering and mechanical details, Mayor writes on this in the last chapter, but this book might not quite be what you hoped for. As she explains, the ancient Greeks imagined their gods capable of crafting robots without necessarily explaining how these were supposed to work, the gods’ expertise being beyond scrutiny. This area is not my speciality, but good starting points might instead be The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, the somewhat dated Technology in the Ancient World and Engineering in the Ancient World, and the hard-to-find Ancient Greek Technology: The Inventions of the Ancient Greeks.

On the flip side, coming from Princeton University Press, at least you know you will get thorough and serious scholarship. Any casual foray into the subject of ancient technology quickly descends into speculative ideas on the function of pyramids, borderline conspiracy theories about alien visitations, and before you know it you are reading Von Däniken.

“[…] the ancient Greeks imagined their gods capable of crafting robots without necessarily explaining how these were supposed to work, the gods’ expertise being beyond scrutiny.”

With these caveats in mind, what do you get? A mightily interesting look into the minds and thoughts of ancient Greeks, that is what. As Mayor says in her introduction, you might think that myths of artificial life refer to inert matter brought to life by the will of a god, but she makes a strong point that much mythology refers to products of  manufacture. Although she hesitates to consider all such myths direct precursors of modern technology, it should come as no surprise that people’s frame of reference at the time is reflected in their mythology.

manufacture. Although she hesitates to consider all such myths direct precursors of modern technology, it should come as no surprise that people’s frame of reference at the time is reflected in their mythology.

Using a rich iconography, Mayor illustrates the various myths with photos of decorated coins, vases, gems, mirrors, and other objects. To the point that next time you visit a history museum, you will want to look twice at the ancient Greece section. Amidst the many regular depictions of gods and mythical creatures, there are some truly remarkable details that are easily overlooked. Mayor opens with the bronze giant Talos who was said to patrol the borders of Crete. Despite his origins, he turns out to be susceptible to all-too-human ruses and is destroyed by removing a bolt in his ankle, suggesting similarities to the story of Achilles. This causes him to “bleed out” his ichor, a vital substance akin to blood. Possibly this reflects ancient metallurgy techniques, though it also reminds one of the state of physiological knowledge of our circulation system back then.

“An important figure is Daedalus, a prolific tinkerer […] who fashioned Icarus’s wings. But few will know him for the first cow sexbot.”

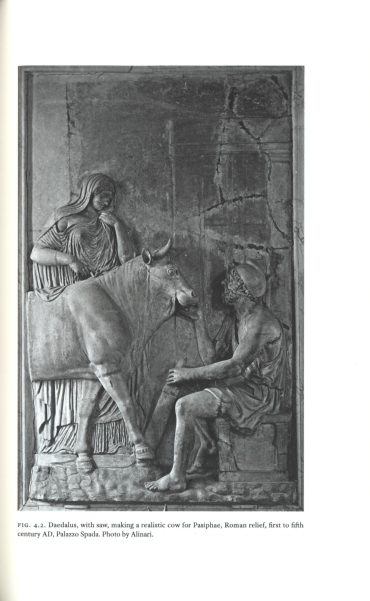

An important figure is Daedalus, a prolific tinkerer. Mayor reminds us that, as with most cases, the surviving literature and other evidence is incredibly fragmentary, so opinions are divided on whether he was a real person, a mythical character, or even a group of inventors. Regardless, you will know him, for it is he who fashioned Icarus’s wings. But few will know him for the first cow sexbot.

Those Greeks.

It does make you wonder whether Princeton’s recent The Book of Greek & Roman Folktales, Legends, & Myths comes with a content warning. So, the adulterous King Minos, who ruled over the same Crete patrolled by the above Talos, was cursed by his wife Pasiphae. Any attempt at extra-marital sex would result in him ejaculating scorpions, millipedes, and snakes. Pasiphae, in turn, was punished by Zeus to lust after a bull in Minos’s herd. To satisfy her cravings she turns to Daedalus to make her a hollow replica of a cow that she can crawl into and that the bull can then mount. I will leave those working in the livestock industry, who use similar devices to collect semen from  bulls for use in artificial insemination, to ponder the deep roots of their profession.

bulls for use in artificial insemination, to ponder the deep roots of their profession.

Daedalus was so good at making his statues life-like that the theme of statues escaping their plinths became, well, a running gag in period dramas. But it also led to Socrates questioning whether such automata should be tethered to prevent them from escaping like runaway slaves. Mayor sees parallels to current conundrums. Are we comfortable considering robots and artificial intelligence (AI) as property, or even slaves? And who, then, is responsible for their actions? Early accidents with self-driving cars have already shown that this is no mere academic question.

“Who is responsible for the actions of AI? Early accidents with self-driving cars have already shown that this is no mere academic question.”

Similarly, Homer’s Odyssey describes Uncanny Valley-type responses (the unease felt towards life-like androids) millennia before roboticist Masahiro Mori first coined this term in 1970. More sexbots feature in the Pygmalion myth, which introduces the wonderful term algamatophilia, or statue lust. Mayor quotes classicist and psychologist Alex Scobie, who makes the point that this “arose at a time when Greek and Roman sculptural artistry achieved high degrees of realism and idealized beauty”. It made me wonder about the parallels that can be drawn to current concerns over the idealized portrayal of (especially) women in advertising, where all imperfections are airbrushed  out and people’s proportions can be photoshopped.

out and people’s proportions can be photoshopped.

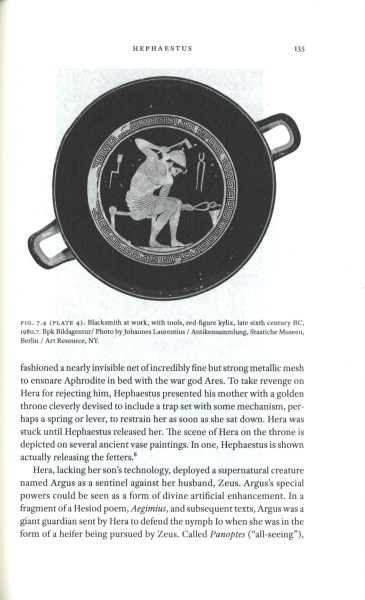

Another important and relevant character in the Greek pantheon is Hephaestus, the god of, amongst others, metalworking, stone masonry, forges, and sculpture. A real maker god. Mayor describes a remarkable array of devices, including automatic gates, self-moving tripods (used by the Greeks to rest cauldrons on), life-like servants, and, most importantly, Pandora. Yes, she of the box – or more likely a large jar. A separate chapter tells her fascinating story, and I realised how little I knew about her: a robot sent on a retribution mission by Zeus, to punish Prometheus for stealing the fire of the gods.

“algamatophilia, or statue lust […] “arose at a time when Greek and Roman sculptural artistry achieved high degrees of realism and idealized beauty””

Amidst this plethora of automata and robots, two early chapters on the Greek obsession with eternal youth and immortality stand out somewhat. These deal less with imagined devices – though there is a magic cauldron promising rejuvenation – and more with the philosophical questions these prospects raise. Interestingly, the idea of “overliving” caused the Greeks more anxiety than that of mortality (see also Mocked with Death: Tragic Overliving from Sophocles to Milton).

Gods and Robots turned out to be a fascinating book on an unusual subject. There are certainly parallels to be drawn to current thinking and concerns about AI and robots (see also In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? the History and Future of Artificial Intelligence) though Mayor is careful not to overstate her case. I think that especially those interested in, or currently reading, Greek mythology will find interesting context in this book. I know I have been terribly tempted by the recent release of a smart-looking boxed set from the University of California Press containing The Iliad and the Odyssey. And when I finally cave and get that, I know Mayor’s work will have prepared the way for better understanding some of what I will read there.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

You can support this blog using below affiliate links, as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases:

, ebook or audiobook

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>