Given that we are nothing but mammals, it is perhaps understandable that humans are rather mammal-centric, something that conservation organisations capitalise on. But where palaeontology is concerned, dinosaurs get all the love. And that does early mammals little justice says Scottish palaeontologist and Palaeocast co-host Elsa Panciroli. Far from mere bit players cowering in the shadows of these “terrible lizards”, mammals have a long and rich evolutionary history that predates the dinosaurs but is poorly known outside of specialist circles. Panciroli’s debut changes all that and does so in a most readable and immersive fashion.

Beasts Before Us: The Untold Story of Mammal Origins and Evolution, written by Elsa Panciroli, published in Europe by Bloomsbury Publishing in June 2021 (hardback, 320 pages)

To pick up the tale of mammal evolution, Panciroli takes you all the way back to the Carboniferous (roughly 360–300 million years ago) when higher oxygen levels supported a land of giants. It was here that the first fish made landfall and tetrapods evolved. To get from this distant ancestor to modern mammals, you have to follow the story through groups whose names are likely unfamiliar. To help you visualise these, stylish illustrations from April Neander open each chapter, while the endpapers* provide a helpful family tree drawn by Marc Dando. These do not list all mentioned groups but do present the big picture and I found myself referring to them frequently.

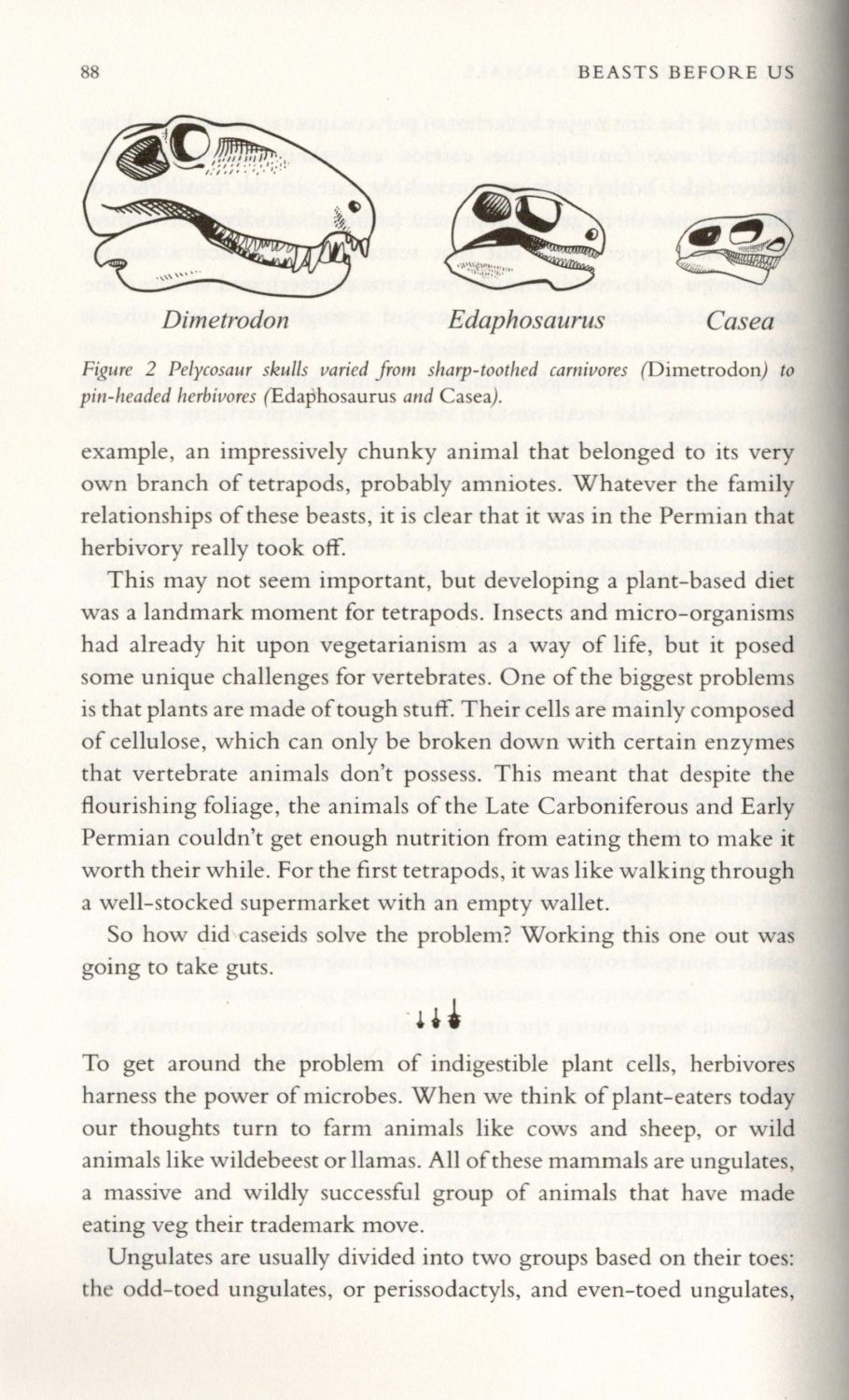

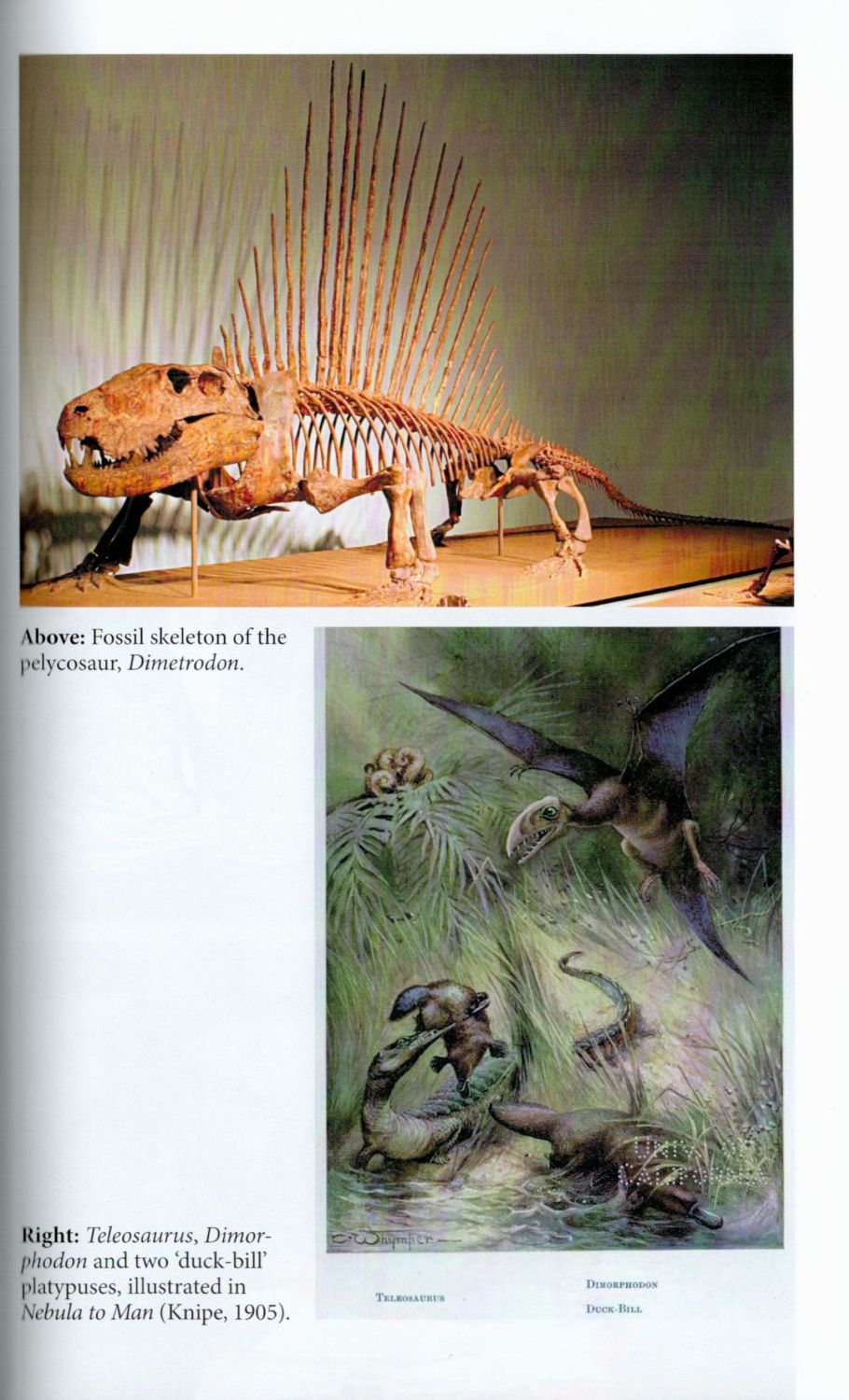

Thus we get to meet the synapsids, one of which you will know: the sail-backed, no-it-is-not-a-dinosaur Dimetrodon. Synapsids included the pelycosaurs (also not dinosaurs), which gave rise to the therapsids: carnivores with more powerful jaws and a stronger bite. Some of these, including the gorgonopsians, pioneered sabre-teeth, proving later groups to be mere copy-cats. Convergent evolution is, quite literally, a recurrent theme that Panciroli mentions whenever she can get away with it. Various therapsids were also the first groups to evolve endothermy or warm-bloodedness, though “like so many of the features associated with mammals [it] emerged scattershot. It wasn’t switched on like a lightbulb, lighting up all therapsids at once” (p. 120).

Thus we get to meet the synapsids, one of which you will know: the sail-backed, no-it-is-not-a-dinosaur Dimetrodon. Synapsids included the pelycosaurs (also not dinosaurs), which gave rise to the therapsids: carnivores with more powerful jaws and a stronger bite. Some of these, including the gorgonopsians, pioneered sabre-teeth, proving later groups to be mere copy-cats. Convergent evolution is, quite literally, a recurrent theme that Panciroli mentions whenever she can get away with it. Various therapsids were also the first groups to evolve endothermy or warm-bloodedness, though “like so many of the features associated with mammals [it] emerged scattershot. It wasn’t switched on like a lightbulb, lighting up all therapsids at once” (p. 120).

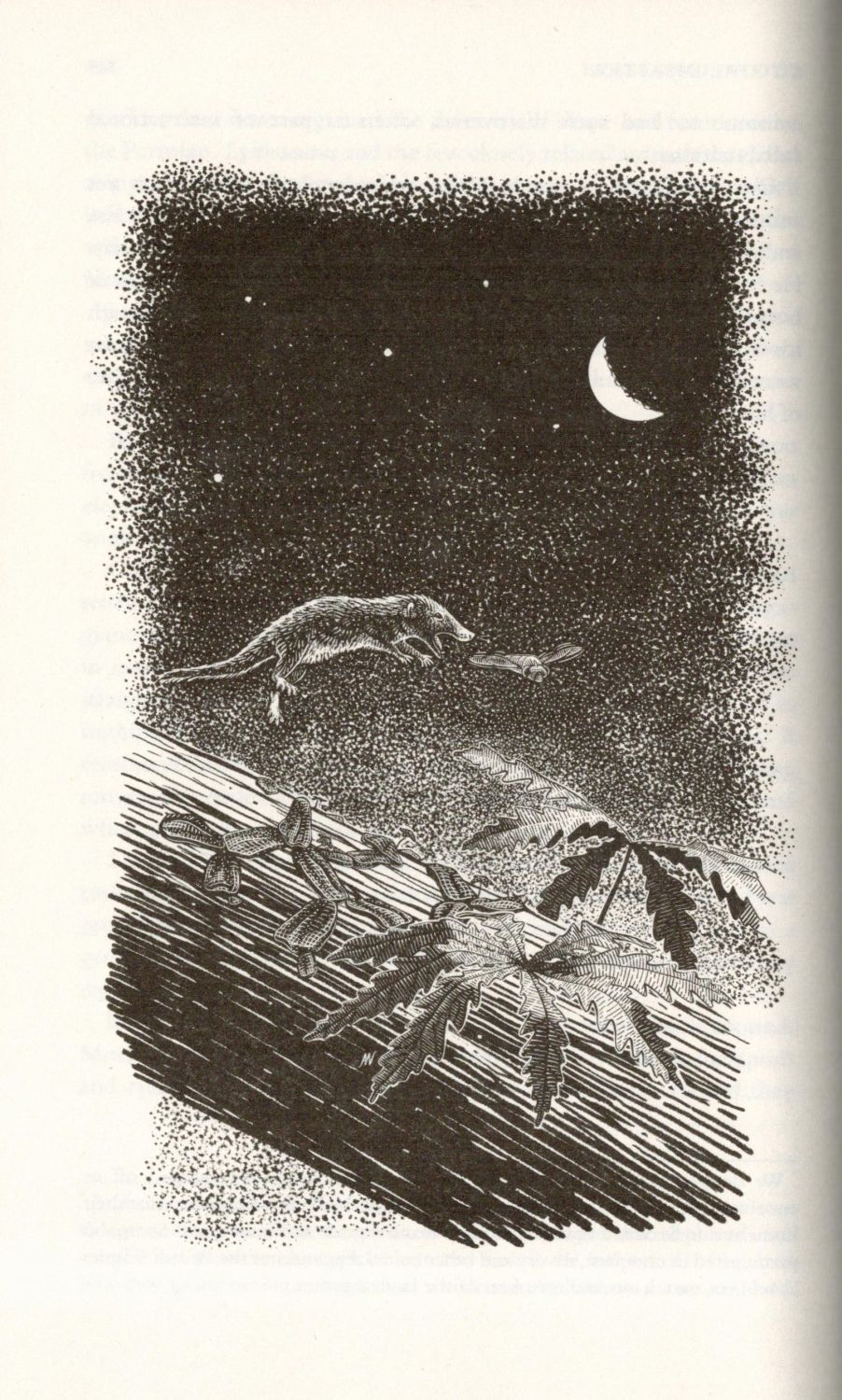

As the end-Permian mass extinction wiped the slate clean, the age of reptiles had begun. But some of our mammal ancestors survived. Rising like a phoenix from the ashes were, amongst others, the dicynodonts, who would have looked you in the eye from behind tusks and a turtle-like beak. One particularly successful group, possibly because it dug burrows, was Lystrosaurus, a genus that in the early Triassic made up 90% of all vertebrates. A related group, the cynodonts, is largely responsible for the misconception that our ancestors were insignificant during the reign of the dinosaurs, as they evolved to be smaller. But this was a feature, not a bug: “With no space among the giants, they took a different route: they perfected being tiny” (p. 163). They exploited the safety of the night, became nocturnal, and developed sensitive eyes. They also lost some ribs and developed a waist, allowing for more flexibility in their locomotion—early synapsids had ribs all the way down.

“[One] group, the cynodonts, is largely responsible for the misconception that our ancestors were insignificant during the reign of the dinosaurs, as they evolved to be smaller. But this was a feature, not a bug”

The Jurassic saw groups such as tritylodontids, docodontans, and multituberculates flourish. As their names imply, these groups experimented with tooth morphology, which later became important diagnostic fossil characters. None of them left living descendants. Instead, it was the therians who were our direct ancestors, but they did not diversify until after the K–Pg boundary. Interestingly, Panciroli suggests** that it was not the dinosaurs that kept the therians in check, but competition from all the other Jurassic mammal groups. This more recent history of the adaptive radiation into modern marsupials and placental mammals is well known, so she purposefully ends the book where most others start the story of mammal evolution .

This brief exercise in name-dropping provides only a snapshot of what Panciroli discusses, and she does a far better job of it. She weaves in the history of fossil discovery and her own work at dig sites in South Africa and Scotland, or labwork at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France. Next to telling the story of mammal evolution, Panciroli also takes on the task of disarming and deconstructing a large amount of cultural and linguistic baggage, with two issues standing out.

This brief exercise in name-dropping provides only a snapshot of what Panciroli discusses, and she does a far better job of it. She weaves in the history of fossil discovery and her own work at dig sites in South Africa and Scotland, or labwork at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France. Next to telling the story of mammal evolution, Panciroli also takes on the task of disarming and deconstructing a large amount of cultural and linguistic baggage, with two issues standing out.

First, as part of a younger generation of scientists, Panciroli is keen to decolonise her discipline. This means acknowledging that the scientific collections on which she herself works are the spoils of empire. Our museums are filled with colonialist plunder. Especially in the first chapter, where she gives a potted history of geology and biology, she repeatedly points to the imperialist framework in which these disciplines were born and how that has shaped conventions and biases to this day. Celebrated figureheads such as Buckland, Darwin, Lyell, Cuvier, Hutton, Lamarck, Owen etc. simultaneously held ideas now considered unsavoury, and they rarely credited Indigenous knowledge or help in the acquisition of fossils. Furthermore, as a woman, she has a few things to say about diversity. Like many academic disciplines, palaeontology remains largely populated by white, Western men, and it has been hard to shake off the image of the “stereotypical male adventurer” and his “macho plundering of the past” (p. 249). Fortunately, the contributions of women are increasingly being acknowledged, and Panciroli here celebrates Polish Mesozoic mammal researcher Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska who was the first woman to lead fossil collection expeditions in Mongolia.

“[…] the long history of evolutionary theory means that outdated modes of thinking continue to permeate our language. […] Panciroli similarly uses every opportunity to remind you that evolution is not goal-directed”

Second, the long history of evolutionary theory means that outdated modes of thinking continue to permeate our language. She shudders at the term “mammal-like reptiles” still used to describe the synapsids: “This first amniote tetrapod was neither mammal nor reptile—neither of those groups had evolved yet” (p. 61). We did not evolve from reptiles, nor are they more primitive compared to us. Panciroli similarly uses every opportunity to remind you that evolution is not goal-directed: “It is random, the route forged by happenstance” (p. 57). It has proven hard to let go of the Scala Naturae, the idea of a linear series of improvements, “like an assembly-line through time” (p. 120) leading ultimately to the perfect organism: us.

This neatly leads to my last observation: Panciroli’s writing is sublime. Her prose is concise without being stunted, her visual metaphors rich without being flowery. Of the late Triassic mammals she writes: “These tiny ancestors were living microchips. They were night-vision goggles. They were fuzzy little ninjas, wielding shuriken teeth to reap their insect prey in silence and stealth” (p. 171). On the break-up of Pangaea: “After their epic 250 million-year snuggle, the continents of Earth were parting ways […] By the end of the Jurassic, the whole world was unzipping itself, with new seas and oceans splashing into the gaps” (p. 203). On the K–Pg event: “The universe drew an iridium line under things. From here on, life would be different” (p. 274). And her description of the tritylodontid herbivore niche is just beautiful: “All of the non-mammalian cynodonts had turned to dust, except for the tritylodontids […]. Natural selection had moulded them into premier leaf-grinding machines. Of course there had been synapsid herbivores before […] but those bulky predecessors were gone. In the world of crocs and dinosaurs, mammals had microscoped themselves into the understorey, and the tritylodontids were left to eat the scenery” (p. 237).

This neatly leads to my last observation: Panciroli’s writing is sublime. Her prose is concise without being stunted, her visual metaphors rich without being flowery. Of the late Triassic mammals she writes: “These tiny ancestors were living microchips. They were night-vision goggles. They were fuzzy little ninjas, wielding shuriken teeth to reap their insect prey in silence and stealth” (p. 171). On the break-up of Pangaea: “After their epic 250 million-year snuggle, the continents of Earth were parting ways […] By the end of the Jurassic, the whole world was unzipping itself, with new seas and oceans splashing into the gaps” (p. 203). On the K–Pg event: “The universe drew an iridium line under things. From here on, life would be different” (p. 274). And her description of the tritylodontid herbivore niche is just beautiful: “All of the non-mammalian cynodonts had turned to dust, except for the tritylodontids […]. Natural selection had moulded them into premier leaf-grinding machines. Of course there had been synapsid herbivores before […] but those bulky predecessors were gone. In the world of crocs and dinosaurs, mammals had microscoped themselves into the understorey, and the tritylodontids were left to eat the scenery” (p. 237).

Beyond a few academic textbooks and technical monographs, the deep evolutionary history of mammals has remained largely hidden in the academic literature. Beasts Before Us unleashes their story most spectacularly and engagingly. This beautifully written debut marks Panciroli as a noteworthy new popular science author. May this be the first of many books! You might also want to check out my Q&A with Panciroli published over at the NHBS Conservation Hub.

* Illustrated endpapers are one of my favourite features in a book, and one that, I think, too few publishers and authors use.

** The paper arguing this, still in press when she wrote this book, has just been published in Current Biology.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>In the field of palaeoanthropology, one name keeps turning up: the Leakey dynasty. Since Louis Leakey’s first excavations in 1926, three generations of this family have been involved in anthropological research in East Africa. In this captivating memoir, Meave, a second-generation Leakey, reflects on a lifetime of fieldwork and research and provides an inspirational blueprint for what women can achieve in science.

The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past, written by Meave Leakey and Samira Leakey, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in November 2020 (hardback, 396 pages)

With The Sediments of Time, Meave* follows a family tradition. Her husband Richard, and his parents Louis and Mary have all been the subject of (auto)biographies, now many decades old. Science writer Virginia Morell later portrayed the whole family in her 1999 book Ancestral Passions. Much has happened in the meantime, and though this book portrays Meave’s personal life, it heavily leans towards presenting her professional achievements, as well as scientific advances in the discipline at large. Thus, Meave’s childhood and early youth are succinctly described in the first 15-page chapter as she is keen to get to 1965 when a 23-year-old Meave starts working with Louis in Kenya.

Whereas Louis and Mary were famous for their work in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Richard and Meave have made their careers around Lake Turkana in northern Kenya. The first two parts of the book take the reader chronologically through the various excavation campaigns. These include the decade-long excavations in and around Koobi Fora, one highlight of which was the find of Nariokotome Boy (also known as Turkana Boy), a largely complete skeleton of a young Homo erectus. The subsequent campaign in Lothagam yielded little hominin material but did reveal a well-documented faunal turnover of herbivore browsers being replaced by grazers with time. Meave has also described several new hominin species. This includes Australopithecus anamensis, which would be ancestral to Australopithecus afarensis (represented by the famous Lucy skeleton), and Kenyanthropus platyops, which would be of the same age as Ardipithecus ramidus. That last name might sound familiar, because…

“Woven into Meave’s narrative of exploration and excavation is an overview of how palaeoanthropology developed as a discipline, and what are some of its big outstanding questions.”

Having just reviewed Fossil Men, which portrayed the notorious palaeoanthropologist Tim White, I was curious to see what Meave had to say about him. In Fossil Men, Kermit Pattison already mentioned that she described White “with a note of sympathy” (p. 5), and she affirms that picture here, writing that he is “a meticulous scientist […] intolerant of bad science […] outspoken and frank […] although he was charming and a gentleman in less formal situations” (p. 136). And though they meet more than once to compare fossils, notes, and ideas, they remain at loggerheads over certain claims.

Woven into Meave’s narrative of exploration and excavation is an overview of how palaeoanthropology developed as a discipline, and what are some of its big outstanding questions. A recurrent theme is the influence of climate on evolution, often by impacting diet and available food sources. There is the difficult question of naming species and how much difference is enough to recognise a separate species, which ties into the whole lumpers vs. splitters debate in taxonomy. The latter readily name new species whereas the former (White being an example) point to sexual dimorphism and morphological variation and recognize only one or very few hominin species. Your stance in that debate affects what you think of Meave’s descriptions of Au. anamensis as being part of a lineage towards Au. afarensis, and whether K. platyops is a species distinct from Ar. ramidus (White obviously thinks not).

This discussion of topics relevant to palaeoanthropology strongly comes to the fore in the book’s third part, by which time Meave is examining the Homo lineage and the question where we appeared from. This sees her tackling topics such as human childbirth and the role of grandmothers, Lieberman’s hypothesis of endurance running as a uniquely human strategy to run prey to exhaustion, palaeoclimatology and the mechanism of the Milankovitch cycles, the spread of Homo erectus around the globe (the Out of Africa I hypothesis), and the use of genetics to trace deep human ancestry. I feel that Meave overstretches herself a little bit in places here. Though her explanations are lucid and include some good illustrations, some relevant recent literature, on e.g. ancient DNA and Neanderthals is not mentioned.

“Meave can draw on a deep pool of remarkable and amusing anecdotes that are put to good use to lighten up the text. And though the focus is on her professional achievements and the science, real life interrupts work on numerous occasions.”

Meave can draw on a deep pool of remarkable and amusing anecdotes that are put to good use to lighten up the text. And though the focus is on her professional achievements and the science, real life interrupts work on numerous occasions. Some of these are joyful, such as the birth of her daughters Louise and Samira. Some are a mixed blessing, such as Richard’s career changes, first when Kenya’s president hand-picks him to lead the Kenya Wildlife Service and combat rampant elephant poaching, then when he switches to attempting political reform. It removes him from palaeoanthropology and their time together in the field. Other occasions are outright harrowing, such as Richard’s faltering kidneys that require transplantations, or the horrific plane crash that sees him ultimately lose both legs despite extended surgery.

Illustrator Patricia Wynne contributes some tasteful drawings to this book, though the figure legends do not always clarify the important details these images try to convey. And I would have loved to see some photos of important specimens, whether during excavation or after preparation, especially given how much Meave focuses on the scientific story in this book. Many specimens are described in great detail but the colour plate section mostly contains photos of the Leakeys and collaborators in the field. Another minor point of criticism is that I was not clear on Samira’s part in writing this book. The dustjacket mentions her as a co-author, but the story is told exclusively through Meave’s eyes, and the acknowledgements do not clarify Samira’s role. I am left to surmise that Meave and Samira together drew on their store of memories for this book.

These minor criticisms notwithstanding, I found The Sediments of Time an inspiring memoir that provided a (for myself long-overdue) introduction to the Leakey dynasty. Meave has led a charmed existence and she is a fantastic role model for women in science.

* I normally refer to authors by their last name but, for obvious reasons and with all due respect, I will be deviating from that habit here and mention the various Leakeys by their first name.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>Charismatic as big cats might be, their origins and evolutionary history are still not fully understood. In a mind-bogglingly beautiful marriage of art and science, On the Prowl provides a current overview of big cat evolution that will have many a book lover purring with pleasure.

On the Prowl: In Search of Big Cat Origins, written by Mark Hallett and John M. Harris, published by Columbia University Press in June 2020 (hardback, 259 pages)

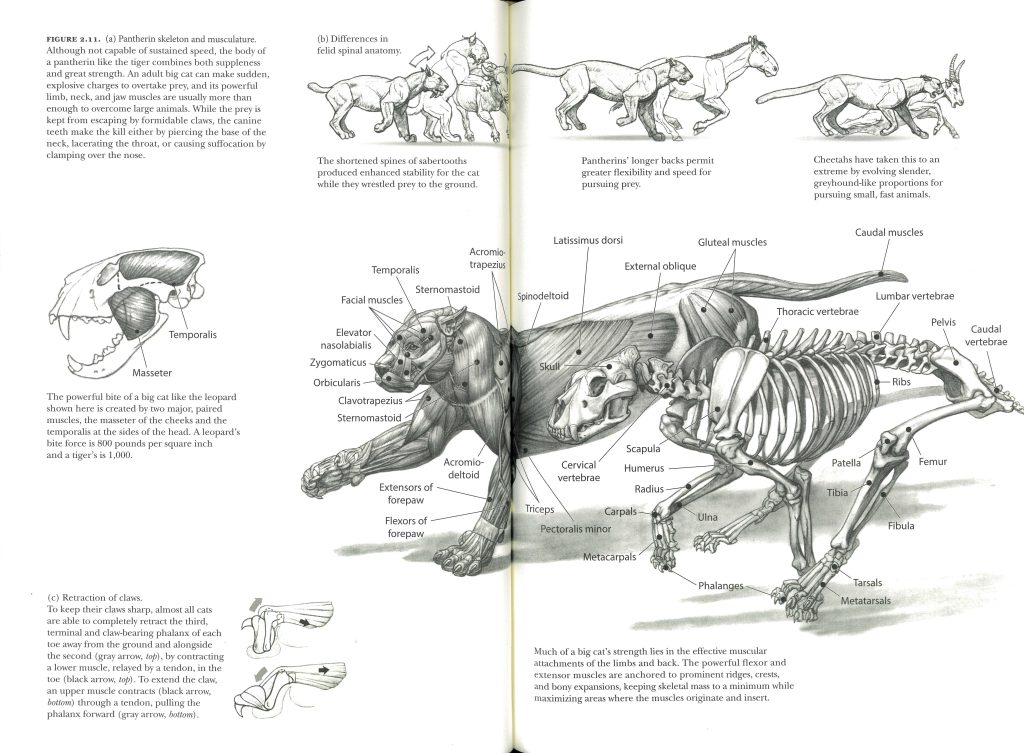

Before I even get to the contents of the book I simply have to first highlight the artwork. On the Prowl is authored by naturalist and scientific artist Mark Hallett and geologist and emeritus curator John M. Harris, with Hallett additionally providing artwork. And these are not mere pretty decorations.

Oh my, where do I even begin?

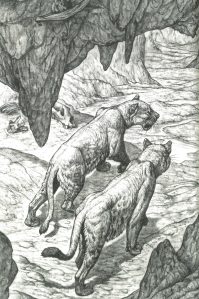

This is the rare category of tastefully executed scientific illustrations: anatomical drawings, behavioural sequences, phylogenetic trees, maps, reconstructions of life appearance, and beautiful full-bleed (i.e. printed edge-to-edge) pictures opening each chapter. Every drawing, full of detail, has been carefully crafted, has a function in the book, and has been drawn in the same tasteful pencil-sketch style. Jaw-dropping? Gob-smacking? You pick your favourite superlative—I was floored when I first opened this book. Basically, do not browse through this if you were planning not to buy more books this month, because it will be very hard to put it back down.

This is the rare category of tastefully executed scientific illustrations: anatomical drawings, behavioural sequences, phylogenetic trees, maps, reconstructions of life appearance, and beautiful full-bleed (i.e. printed edge-to-edge) pictures opening each chapter. Every drawing, full of detail, has been carefully crafted, has a function in the book, and has been drawn in the same tasteful pencil-sketch style. Jaw-dropping? Gob-smacking? You pick your favourite superlative—I was floored when I first opened this book. Basically, do not browse through this if you were planning not to buy more books this month, because it will be very hard to put it back down.

But what of the actual writing? On the Prowl spends five chapters tracing the outline of big cat evolution during the last 23 million years. The last three chapters deal, notably, with recent declines and extinctions, and current conservation concerns. The focus here is on the pantherines or subfamily Pantherinae; the lions, tigers, jaguars, leopards, and snow leopards. Not discussed in as much detail and acting more as supporting cast are the Felinae (pumas, cheetahs, and smaller genera such as lynxes, ocelots, clouded leopards etc.) and the various sabertoothed cats. Seeing the number of books already dealing with these (Anton’s Sabertooth and the two edited collections from Johns Hopkins University Press) it is easy to agree with their decision not to focus any further on sabertooths here.

“I simply have to first highlight the artwork […] This is the rare category of tastefully executed scientific illustrations […] I was floored when I first opened this book”

The story of pantherine evolution is far from fully resolved, and this part of the book required close attention and occasional rereading. The various lineages and subspecies, notable fossil finds, and competing hypotheses all make for a rather complicated story full of details. I should add that I am not faulting Hallett and Harris’s writing, as they do an admirable job distilling a lot of technical literature into a very readable book. It is simply that, much as we might like a good narrative, reality is often unruly and does not yield to a clean, neat story. Biology is messy like that. But what a story it nevertheless is!

An introductory overview gets you up to speed on early carnivore and carnivoran evolution and explains the difference between the two. The first cat-like species you then meet is the genus Proailurus, which (likely) evolved into Pseudalaerus, the potential ancestor to all the big cats and the “true” sabertooth cats (the machairodontines, which includes the famous Smilodon). At the time, these faced stiff competition from the so-called “false” sabertooth cats, the nimravids and barbourofelids.

An introductory overview gets you up to speed on early carnivore and carnivoran evolution and explains the difference between the two. The first cat-like species you then meet is the genus Proailurus, which (likely) evolved into Pseudalaerus, the potential ancestor to all the big cats and the “true” sabertooth cats (the machairodontines, which includes the famous Smilodon). At the time, these faced stiff competition from the so-called “false” sabertooth cats, the nimravids and barbourofelids.

Personal revelation number one: I was ignorant of the fact that not all sabertooths are closely related (had I actually read Mauricio Anton’s Sabertooth, I would know all this). The family Nimravidae arose very early, some 50 million years ago, and is technically merely a cat-like carnivore. The subfamily Machairodontinae split off from the cat family Felidae some 16 million years ago and is technically a true cat. Despite this taxonomical distance, they came to closely resemble each other. (Whoever said that what looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, probably is a duck never heard of convergent evolution…).

“it is starting to look that the Tibetan Plateau was ground zero for the pantherines from which both the snow leopard–tiger and the jaguar–lion–leopard lineages dispersed globally.”

What probably gave the Felidae the competitive edge was changes in climate and, with it, vegetation: closed forests gave way to open woodlands and savannas. Chapter 2 describes in marvellously illustrated detail the anatomical and behavioural adaptations of the pantherines that made them such formidable hunters in these open habitats and helped them claw their way to the top. This placement of big cat evolution in the context of their ecosystems and their relationship to other animals is a recurring and very welcome theme in this book. The earliest known pantherine we then meet is Panthera blytheae, a possible ancestor of the modern snow leopard, which brings me to…

Personal revelation number two: it is starting to look that the Tibetan plateau was ground zero for the pantherines from which both the snow leopard–tiger and the jaguar–lion–leopard lineages dispersed globally. Two appendices give an illustrated overview of felids in geologic time and pantherin dispersal across the world. These are useful, but, like executive summaries, are very condensed. I would have loved a few more detailed illustrations of the various timelines over which this happened, breaking out the individual lineages.

Personal revelation number two: it is starting to look that the Tibetan plateau was ground zero for the pantherines from which both the snow leopard–tiger and the jaguar–lion–leopard lineages dispersed globally. Two appendices give an illustrated overview of felids in geologic time and pantherin dispersal across the world. These are useful, but, like executive summaries, are very condensed. I would have loved a few more detailed illustrations of the various timelines over which this happened, breaking out the individual lineages.

Now, connoisseurs might have immediately perked up their ears when hearing of this book. How does it compare to the 1997 book The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives? This was, incidentally, also published by Columbia University Press, and similarly combined beautiful artwork with accessible text. It is one of the first things the authors tackle, writing that it focused more on the true felid and the nimravid cats, and comparing the books indeed confirms this. I can see two reasons why owners of the 1997 book want to pick up this one as well. One is that it fills you in on the intervening 23 years of scientific research, especially that coming out of the Asian palaeontology community. Panthera blytheae was only discovered in 2010, and pinpointing the Tibetan Plateau as the centre of pantherine radiation strikes me as a significant advance in our understanding. Two, On the Prowl spends a substantial chunk dealing with both recent extinctions and conservation concerns, something that the previous book mentioned only briefly at the end.

“Having told the story of big cat evolution, it would have been an oversight to turn a blind eye to the massive losses caused by human greed and cruelty.”

Having told the story of big cat evolution, it would have been an oversight to turn a blind eye to the massive losses caused by human greed and cruelty. Thus, these chapters and their no-punches-pulled tone are fully justified. One chapter focuses on the early decline following the last ice age, in particular discussing the decline of the steppe lion (of the four discussed extinction scenarios, only one involves humans). I was somewhat surprised to see only minimal mention of Paul Martin’s overkill hypothesis when drawing a comparison to the fate of the American lion, Panthera atrox, and no mention at all of End of the Megafauna that critically discussed it. A second chapter picks up the story of extinction with the slaughter of big cats in Roman amphitheatres and habitat destruction ever since agriculture took off some ten thousand years ago. It also prominently mentions the huge impact of trophy hunting by western colonialists in Africa and Asia. The last chapter highlights the ongoing threats of poaching and wildlife trafficking (particularly slamming tiger farms in China and the canned lion hunting industry in Africa), human-wildlife conflict between carnivores and cattle herders, the shortcomings of national parks, and reasonable and critical consideration of future options such as captive breeding, rewilding, and de-extinction.

Having told the story of big cat evolution, it would have been an oversight to turn a blind eye to the massive losses caused by human greed and cruelty. Thus, these chapters and their no-punches-pulled tone are fully justified. One chapter focuses on the early decline following the last ice age, in particular discussing the decline of the steppe lion (of the four discussed extinction scenarios, only one involves humans). I was somewhat surprised to see only minimal mention of Paul Martin’s overkill hypothesis when drawing a comparison to the fate of the American lion, Panthera atrox, and no mention at all of End of the Megafauna that critically discussed it. A second chapter picks up the story of extinction with the slaughter of big cats in Roman amphitheatres and habitat destruction ever since agriculture took off some ten thousand years ago. It also prominently mentions the huge impact of trophy hunting by western colonialists in Africa and Asia. The last chapter highlights the ongoing threats of poaching and wildlife trafficking (particularly slamming tiger farms in China and the canned lion hunting industry in Africa), human-wildlife conflict between carnivores and cattle herders, the shortcomings of national parks, and reasonable and critical consideration of future options such as captive breeding, rewilding, and de-extinction.

Overall, On the Prowl provides a superb overview of the complex and rich story of big cat evolution, while being an outstanding showcase of how beautiful artwork can support science communication. I have no hesitation to recommend this book as one of 2020’s must-buy palaeontology books.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>

“End of the Megafauna: The Fate of the World’s Hugest, Fiercest, and Strangest Animals“, written by Ross D.E. MacPhee and illustrated by Peter Schouten, published by W.W. Norton & Company in November 2018 (hardback, 236 pages)

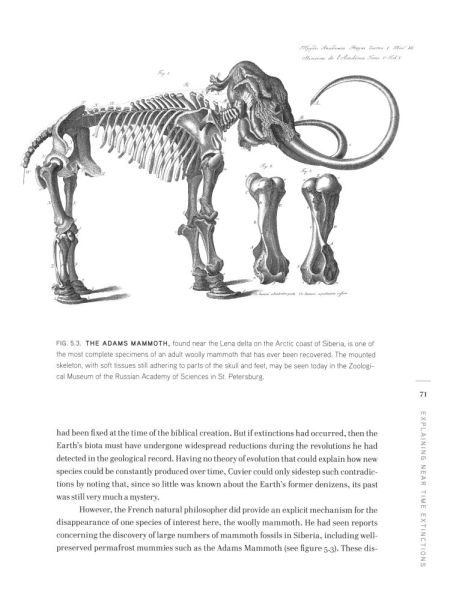

Paul S. Martin (1928-2010) was a palaeoecologist who developed the overkill hypothesis in the 1960s: as our ancestors spread over the planet and entered new lands, they hunted the existing megafauna into extinction. Especially in the Americas there seemed to be a close link between humans appearing and megafauna disappearing. He championed this idea in a career spanning five decades, culminating in his 2005 book Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America. A lot of the ensuing academic discussion has been compiled in the edited volumes Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences (1999) and American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene (2009) to which MacPhee contributed, and on which he now draws in this book.

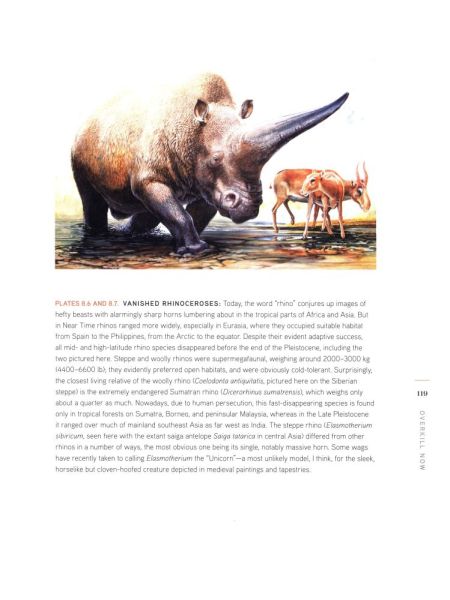

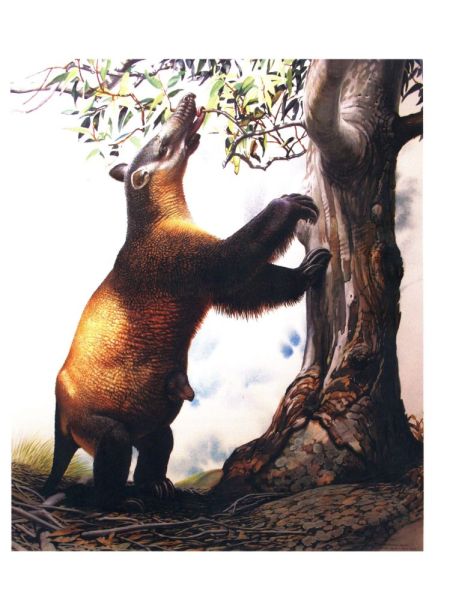

MacPhee first introduces the particular characteristics of our world during the Quaternary (the last 2.6 million years), both its climate with the many ice ages and warmer interglacial periods (see also The Ice Age), and the peculiar megafauna that included giant sloths, enormous flightless birds, and more exotic species such as glyptodonts and gomphotheres, weighing in the hundreds or even thousands of kilograms (see for example Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America, Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys: The Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America, Extinct Madagascar: Picturing the Island’s Past, and Australia’s Mammal Extinctions: A 50,000-Year History). Throughout, the book is illustrated with wonderful plates by Peter Schouten that bring to life the landscapes and animals of this time (though some of them have been spread awkwardly over one-and-a-half pages, obscuring some details).

MacPhee first introduces the particular characteristics of our world during the Quaternary (the last 2.6 million years), both its climate with the many ice ages and warmer interglacial periods (see also The Ice Age), and the peculiar megafauna that included giant sloths, enormous flightless birds, and more exotic species such as glyptodonts and gomphotheres, weighing in the hundreds or even thousands of kilograms (see for example Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America, Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys: The Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America, Extinct Madagascar: Picturing the Island’s Past, and Australia’s Mammal Extinctions: A 50,000-Year History). Throughout, the book is illustrated with wonderful plates by Peter Schouten that bring to life the landscapes and animals of this time (though some of them have been spread awkwardly over one-and-a-half pages, obscuring some details).

The bulk of the book, however, is dedicated to a careful examination of the two leading explanations for the extinctions; climate change and, foremost, overkill. MacPhee walks the reader through the unfolding discussion as opponents poked holes in these ideas and proponents tried to shore them up again with new data. He takes stock of the main objections and the status of the overkill idea today, and puts forward alternative explanations.

Especially based on the peopling of the Americas (see First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America), Martin envisioned a wave of destruction as humans migrated from north to south, from Alaska to Patagonia, in about 1000 years, killing everything in their path – even likening it to a blitzkrieg. He saw this pattern as a template for recent megafauna extinctions around the globe. Dramatic? Yes. Especially extinctions of island dwellers such as the dodo, which are clearly linked to human hunting, lend the idea credibility (see The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions).

“Martin envisioned a wave of destruction as humans migrated […] from Alaska to Patagonia […] killing everything in their path – even likening it to a blitzkrieg”

But, MacPhee points out, upon closer inspection many things don’t add up. Some species that were not hunted (e.g. horses and camels) went extinct, whereas others that were (e.g. bison), survived (only to be almost exterminated in recent times…). Timing is crucial, but findings from archaeology and ancient DNA (see Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past) increasingly suggest that the Americas were populated before the Clovis people moved in 12,000 years ago. In Africa and Eurasia, meanwhile, humans and megafauna “happily” coexisted for thousands of years. Martin furthermore argued for prey naïveté: not having encountered humans before, megafauna supposedly lacked appropriate anti-predator responses. Though observed in island species, it seems implausible in continental animals. The scale and organisation required from bands of hunter-gatherers equipped with stone-age tools to effect a sustained blitzkrieg strains credibility. Ethnographic studies show that humans might band together shortly for annual hunting expeditions, but normally disperse again afterwards. Finally, there is a lack of any archaeological evidence for mass kill sites.

MacPhee concludes that we have reached an intellectual impasse pursuing this research agenda. Though some strong arguments can be made in favour of overkill, and some extinctions no doubt can be attributed to it, there are many and obvious weaknesses when extrapolating this. He discusses some interesting alternative explanations and highlights what data we need moving forward to come to a better answer. The strong suit of this book is not just that it explores the nitty-gritty biological and palaeontological details, but also that it takes a step back to examine the history and nature of the debate itself.

MacPhee concludes that we have reached an intellectual impasse pursuing this research agenda. Though some strong arguments can be made in favour of overkill, and some extinctions no doubt can be attributed to it, there are many and obvious weaknesses when extrapolating this. He discusses some interesting alternative explanations and highlights what data we need moving forward to come to a better answer. The strong suit of this book is not just that it explores the nitty-gritty biological and palaeontological details, but also that it takes a step back to examine the history and nature of the debate itself.

As MacPhee also remarks, catastrophic, single-cause explanations for extinctions are sexy, and the media love the dramatic storytelling it allows. The discussion surrounding the K-Pg extinction 66 million years ago is a point in case (Meteorite impact? Giant volcanic eruptions? Or a bit of both? – see T. rex and the Crater of Doom and The Ends of the World: Volcanic Apocalypses, Lethal Oceans and Our Quest to Understand Earth’s Past Mass Extinctions). And this is not just a rarefied academic discussion. His insight that the overkill hypothesis has shaped our thinking on the current extinction crisis (see The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History) is incisive: staving it off is being cast as a moral duty to redeem ourselves for our past sins of overhunting.

End of the Megafauna is a first-class example of a fantastic popular science book. The combination of a logical structure, accessible writing, shrewd observations, and beautiful illustrations make it a pleasure to read and impossible to put down. Even the glossary makes for an informative read! When I recently reviewed When Humans Nearly Vanished: The Catastrophic Explosion of the Toba Volcano, another example of a catastrophic explanation for observed extinctions, I mentioned being disappointed that Prothero spent so few pages actually discussing the arguments pro and contra. What really makes this book stand out is that MacPhee does it just right: he takes his time to engage with the idea and provides an accessible overview of the arguments for and against. This is, hands-down, one of the best palaeontology books I have read this year and I expect it will be the go-to reference on this topic for years to come.

End of the Megafauna is a first-class example of a fantastic popular science book. The combination of a logical structure, accessible writing, shrewd observations, and beautiful illustrations make it a pleasure to read and impossible to put down. Even the glossary makes for an informative read! When I recently reviewed When Humans Nearly Vanished: The Catastrophic Explosion of the Toba Volcano, another example of a catastrophic explanation for observed extinctions, I mentioned being disappointed that Prothero spent so few pages actually discussing the arguments pro and contra. What really makes this book stand out is that MacPhee does it just right: he takes his time to engage with the idea and provides an accessible overview of the arguments for and against. This is, hands-down, one of the best palaeontology books I have read this year and I expect it will be the go-to reference on this topic for years to come.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

or ebook

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

]]>

“Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth“, edited by Lars Werdelin, H. Gregory McDonald, and Christopher A Shaw, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in July 2018 (hardback, 212 pages)

Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth consists of twelve mostly technical chapters covering a range of topics. Editor H. Gregory McDonald kicks off with the long and convoluted history of the name of the species, with different authorities suggesting different names and affiliations since its initial description in 1842. Nowadays, the consensus is that three species can be recognised, Smilodon fatalis, S. gracilis (both largely North American, but also spilling over into South America), and S. populator (South American). There is also a chapter putting Smilodon in a phylogenetic context, suggesting some very tentative hypotheses as to how it related to other saber-toothed cat groups. Further chapters give detailed description of Peruvian S. fatalis and Chilean S. populator fossils, as well as fossil material from South Carolina. That last chapter argues for reinstating an older species name, going against the consensus I just mentioned.

There is a very readable review of palaeopathological research (i.e. research on fossil traces of injury and disease), and a technical review of its postcranial morphology (i.e. the skeleton minus the skull). This leaves five chapters on those teeth and what they tell us. There are two good reasons for this dental fixation. One, you cannot go around as a cat sporting vampire-like fangs and not expect a bunch of biologists to go apeshit (trust me, I’m a biologist). Two, we have an awful lot of fossil skull material from this group, and skulls, in general, can tell us a lot about the biology of a species. There is one site, in particular, that has contributed disproportionately to our knowledge of Smilodon: the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

“you cannot go around as a cat sporting vampire-like fangs and not expect a bunch of biologists to go apeshit”

Allow me a minor tangent, as I found this bit really interesting. Tar pits are areas where crude oil spontaneously seeps from the earth, forming pools. As lighter fractions of the oil degrade and evaporate, these pools turn into sticky asphalt that can easily trap animals. Trapped animals attract predators and scavengers looking for an easy meal, which in turn run the risk of also becoming trapped. The seepage at La Brea has been happening for tens of thousands of years (side-note: interestingly for such a legendary fossil site, there does not seem to be a good recent book describing it for a general audience as far as I am aware. I am similarly also not 100% clear if these pits are still “active”, but my impression is that they are). Due to their age, the pits have ensnared tens of thousands of animals and in more than a century of excavations, some 5 million (!) fossil specimens large and small have been recovered, including enough fossil bones to, possibly maybe, make up an estimated 3000 S. fatalis individuals.

Point of above little tangent is that La Brea has yielded a huge number of skulls and teeth, but very few articulated fossil skeletons (i.e. fossils where all the bones in the body are still neatly lying in the same orientation as they would have when the animal just died). Instead, La Brea has yielded an enormous unorganised jumble of bones belonging to the rest of the body, explaining the research focus on skulls. Well, that and those teeth of course.

As such, there are chapters here employing fancy new techniques such as computational biomechanics (finite element analysis, since you are asking) to model mechanical stress on the skull and teeth during bites, or steampunk-esque engineering experiments using Robocat (alas, pictures not included!) to do real-life bite tests on carcasses so as to test a proposed hypothesis for how Smilodon might have used those large canine teeth. There are review chapters on tooth development in life – yes, there is enough fossil material to make series of younger to older individuals to see how teeth erupted! And chapters on diet as revealed by dental microwear and isotope analysis of fossil teeth (see also my review of Evolution’s Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins), or changes in feeding ecology over thousands of years as revealed by changes in both tooth breakage and wear, and shape and size of the lower jaw bone.

“much of the material presented in Smilodon is of a highly technical nature […] as such, academic exactitude rather than readability is the prime directive”

The presentation of the book is neat and the reproduction of black-and-white photos and drawings usually excellent. Some tables seem to omit units used for measurements, and do not include explanations of all abbrevations (notably chapter 3 where table footers tell the reader that “N” stands for sample size, but do not add that “MT” stands for metatarsal, for example). Referring to the text will clarify these points, so overall these are minor niggles.

As happens quite often with edited collections of this kind, much of the material presented in Smilodon is of a highly technical nature, aimed at peers. Most chapters assume a detailed knowledge of, in this case, skeletal morphology and dentition and will not clarify jargon, assuming it understood. Next to review chapters, several chapters here are effectively journal articles presenting new research. As such, academic exactitude rather than readability is the prime directive. To give you just one example of what to expect, this from the chapter describing skeletal morphology: “Berta (1987, 1995) noted that S. gracilis has a tuberosity on the anterior margin of the intertrochanteric fossa that is characteristic of Smilodontini and lacking in P. onca” (p. 179). And this goes on for a good ten pages.

Now, to fault the book for this would be completely missing the point. The only reason I am highlighting this is for the reader to know what to expect going in. If you want a popular science book for a general audience, then this is not the book for you – instead, I refer you to Antón’s splendidly illustrated book Sabertooth and, more generally, The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide to their Evolution and Natural History. However, for practising palaeontologists and mammalogists, and tenacious readers who do not flinch at a journal article or two, this book is a treasure trove collecting review articles and new research on Smilodon. And it very neatly complements Naples et al.‘s 2011 book The Other Saber-Tooths: Scimitar-Tooth Cats of the Western Hemisphere, also published by Johns Hopkins University Press, which is a comparable edited collection on Smilodon‘s close relatives.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

]]>